Notes on Army Pay 1642 to 1711

Notes on the History of Army Pay

By LIEUT. -COL. E. E. E. T ODD, O.B.E., R.A.P.C.

A definite establishment of 22,000 men was provided for the "New Model" Army (set up in 1645). To raise this force inducements were held out to disbanded regiments to re-enlist, and chief among them was the promise of regular pay. The Sergeant-Major-General (or Chief of Staff as he would now be called) knew well that pay and efficiency went together. At the same time one quarter of the pay was withheld as security against desertion. This was the origin of "deferred pay."

"Treasurers at War" were instituted to deal with the financial administration, and the General Staff included eight Civilian Treasurers at War with one deputy, under the collective name of "Military Chest."

English soldiers had never been quartered in barracks but lived in inns throughout the country. Under the "New Model" a billet allowance was granted and tariff of prices to be paid by soldiers was drawn up. A proportion of pay was stopped when free quarters were allotted (compare the present [ed. 1932] deduction of it from marriage allowance). Specially constructed buildings for the housing of troops had been customary in Spain under the name of "baraque"; and when Cromwell captured Dunkirk (then in Spanish occupation) and held it as a fort from which to prevent attempts at the invasion of England, his garrison was quartered in the Spanish baraques. Thus the English Army made acquaintance for the first time with life in barracks. They did not, however, become general for many years.

The system of purchase, by which Companies and Regiments were bought and sold for money, persisted with the exiled Royalists but was abolished in England by the Commonwealth. At this period there came into existence the Regimental Agent. Officers on active service were unable to look after their own financial interests and left it to the Agents to draw their pay.

The old system of the Captains making private arrangements for clothing and stopping clothing money from the men's pay remained, but apparently worked satisfactorily. There are in existence records of Courts Martial on cases of fraud; and false muster-rolls were compiled at Dunkirk. But the Protector nearly, if not quite, killed corruption.

By 1647, however, when the immediate purpose of the "New Model" had been realised, the pay of the infantry was 18 weeks in arrears and that of the cavalry 42 weeks. The cry for economy and disbandment, customary in England after every war, forced the hands of the Government who would not or could not find the money. It was proposed to send 12,000 of the troops to Ireland, to pacify that distressful country and incidentally to transfer their charge to the Irish Establishment. But arrears were not mentioned. Mutterings were succeeded by petitions. The offer of six weeks' pay was unavailing. Each regiment elected two "Agitators”, whereon Parliament passed an Act for the immediate disbandment of the entire army, and mutiny broke out.

Portraits of New Model Army generals. Top left, left to right: Robert, Earl of Essex; Alexander, general of the Scots army; Sir Thomas Fairfax; Edward, Earl of Manchester; Bottom, l-r: Philip Skipton; Oliver Cromwell; Waller;

The General Officers of the army, with two officers and two men from each regiment, formed an Army Council under the orders of which the troops advanced on and occupied London. Cavalry in Hyde Park and infantry at Westminster induced the Parliamentary majority to fade away. The question of arrears of pay was lost sight of in the general confusion, and Cromwell put down the mutiny with an iron hand, when troops were required for Ireland, men were given the option of going, or being discharged; all that was done was to pass an act giving vague relief to the financial grievances of the soldiers.

Service in Ireland was followed by service in Scotland and when the battle of Dunbar brought the campaign to a conclusion at the end of 1650, the first English war medal was struck, bearing the figure of Cromwell, and war gratuity was issued to all who had served for the duration of the War.

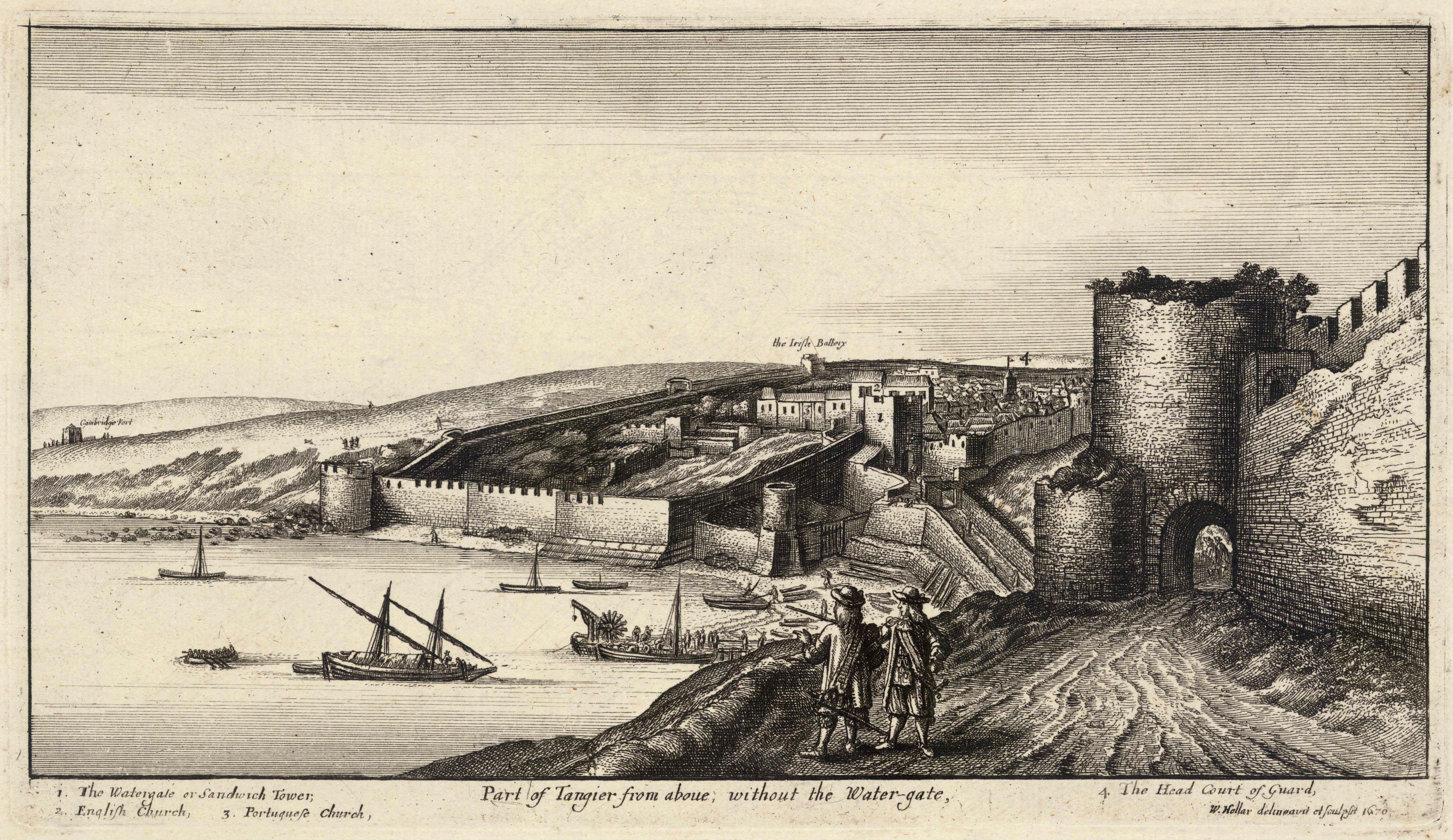

With the Restoration, the Regular Army remained, and for the defence of Tangier against the Moors two new Regiments were raised - now The 1st The Royal Dragoons and The Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey), The old County system was reorganised, the obligation to provide men being graded according to the value of the property owned, The Lord-Lieutenant of the County was given full control of this militia, and a county rate was levied to provide ammunition.

The Restoration saw many changes in Army administration. The former Treasurers at War were replaced by a Paymaster-General, the first of whom was Sir Stephen Fox, with a salary of £400 a year. The Regular Army was as yet unknown to Parliament, and was paid out of the King's privy purse (or out of funds contributed for the payment of the Militia). Charles II being always at his wits end for money, Fox advanced to him on his own private account the weekly pay of the Army in consideration of a commission of 1 shilling in the £. Fox was supposed to be reimbursed by the Treasury at the end of every four months; but payment in full was often overdue, and on the balance outstanding he received interest of 8 per cent, The payment of interest to the Paymaster-General was stopped in 1684, but the poundage on the pay of the troops remained for 150 years. Fox advanced only the pay of the Army. All other military accounts went through the "Treasurer of the armies".

Under the Commonwealth John Rushworth had held the appointment of Secretary to the Council of War. Charles II, before his restoration, followed suit by appointing Sir Edward Nicholas as his Secretary at War, and after the restoration the Sergeant or Secretary at War became permanent. Although a civilian he held a military commission being , subject to the military orders of the King or of the Commander-in-Chief for the time being. His salary was at first 10/ - but after 1669, £1 a day, to include clerical assistance By 1776 , the then Secretary, who previously had been merely a clerk to the Commander-in-Chief arrogated to himself wider powers. The Commonwealth system of centralised control in one man (Cromwell) had disappeared, and in the multitude of General of equal authority the civilian Secretary had perforce to deal with matters that previously had been purely military, e.g., quarters, reliefs and the appointments of envoys. Thus the civilian Secretary obtained an independent footing, and in time became the Minister for War.

The reign, of Charles II and James II witnessed the temporary loss to the British Army of many of the reforms of the Commonwealth period. The financial state returned to the previous confusion, and became worse confounded. The pay of officers and men was consistently in arrear, even to the extent of one year's pay, and officers frequently supplied funds out of their own pockets, with vague hopes of some day being recompensed. The Treasury at this time issued “Treasury tallies” in payment for Army and other services, but in the absence of sufficient public funds to meet them , these tallies could only be sold for cash at discount. Thus the Clothing Contractors gave a discount of 50 per cent, for ready cash rather than accept tallies, About 1697 there were in issue £80,000 worth of tallies which nobody would discount at all . Officers and men suffered severely, in as much as, to get their pay, they had to submit to heavy deductions on account of the discount on the tallies, in addition to all the other charges to which their pay was subjected.

The Army in reality existed on a system of private purchase and payment of fees. Colonels were the proprietors of regiments, and Captains of companies. The civilian clerks depended for their living on fees levied from officers and men. Up to 1663 the very privates paid fees to the recruiting officers. The Secretary-at-War got one fee, the Secretaries of State a second fee from the officer purchasing his commission, and 5 percent of the purchase money was levied from both buyer and seller to finance the new Chelsea Hospital. The subsistence portion of an officer's pay (varying from 75 per cent, in the case of junior ranks to 25 per cent for a major) was payable in advance by the Pay Office with out deduction; but the balance was payable one year in arrear, and was subject to deductions of 1 shilling in the £ to the Paymaster-General, and one day's pay to Chelsea. The Commissary-General of the Musters received one day's pay from all ranks (reduced in 1680 to one-third of a day's pay); the Commissaries charged a fee of two guineas for every troop or company passed at each muster (generally six times a year); and the auditors got 30 shillings for each troop or company on audit of the Paymaster-General's accounts, The financial system of "every functionary living upon everybody else" persisted more or less to the end of the 18th century. It was not till the French Revolution that the maintenance of the War Department was fully recognised as a State liability.

From the days of Queen Mary to those of George III the pay of the Infantry Private (or "Centinel ") was 8d. a day or £12.3s.4d. a year. Of this 6d a day or £9.2s.6d. a year was subsistence money. The remainder, £3.0s.10d., was called "gross off-reckonings," out of which one day's pay went to Chelsea and 5 per cent of the total pay, or 12/2, to the PaymasterGeneral. This left £2.8s.0d., called "net off-reckonings," which " was retained by the Colonel as stoppages for clothing, which included not merely clothing but also sword and belt, bayonet and cartridge-box. These probably cost the Colonel more than that sum; and he had also to pay his own civilian clerk, known as the Colonel's agent. The agent was an embryo Regimental Paymaster, and, like everybody else, got his fee out of Army Pay. Bribes from contractors were customary and there is one instance of an agent bribing his own Colonel to give him, a contract. Not infrequently an officer's death was not reported, so that his pay could still be drawn. By such means, the Colonels quite usually recouped themselves.

Naturally lower ranks followed suit. Captains bribed the Commissaries to pass false musters. A vacancy in the ranks after one muster was not filled till the day before the next muster; and civilians were placed in the ranks to be passed as genuine soldiers . These dummy soldiers were first known as "passe-volants", later "faggots" and later still "warrant-men" in the infantry and "Hautbois" in the cavalry. They were generally known by conventional names- John Doe, Richard Roe or Peter Quib, Charles II also revived the old practice of allowing so many fictitious soldiers or permanent vacancies to a company, for whom pay was drawn.

Half-hearted and ineffective attempts were made to check the most obvious methods of fraud. In 1663 orders were issued to put an end to fraudulent musters. In 1665 the officers of the Board of Ordnance had their salaries increased threefold to lessen the taking of bribes. In 1689 the Colonel of the 13th Foot was cashiered for clothing the Regiment in the condemned clothing of another regiment. But in the same year the Commisary-General, after buying large numbers of horses in Cheshire for the war in Ireland, hired them out to the Cheshire farmers instead of sending them to Ireland, and pocketing the hiring charge. He also drove a lucrative trade in buying salt at 9d. per lb. and selling, it to the War Department at 4/ -. Certain Commisaries advanced money at extortionate rates on interest to officers who could not get their pay, The Commissary-General was arrested but managed to escape punishment. The Commons appointed a Committee of Enquiry and finally passed a Mutiny Act which included penalties against false musters and other frauds.

In 1689 the Treasurer of the Army maintained his own private troop of horse for which he drew pay from public funds as if it were a complete troop. Actually, the troop was made up of himself, two of his clerks who held commissions as officers, and, it is stated, "a standard which he kept in his bedroom". It is also stated that this was the only Corps at the time which received prompt and regular pay. The Treasurer was with the forces in Ireland when inquiries began to be made, but as he was also a member of the House of Commons it appears that he had pressing calls to London whenever he was wanted in Ireland and had to rush off to his duties in Ireland whenever he was wanted in London.

James II attempted to turn all Protestants out of the Army. He failed in England; but in Ireland, which had an establishment of about 7,000 men, no less than 4,000 were discharged and replaced by raw Irish recruits. One regiment alone lost 500 Protestants on the pretext that they were of inferior stature. All these men lost their arrears of pay, and in addition their uniform for which they had paid through "stoppages". Three hundred officers most of whom had purchased their Commissions, were discharged. Large numbers of all ranks who had been dismissed proceeded to Holland, and in due time returned to England under the flag of William of Orange.

The reigns of William and Anne saw the appointment by the House of Commons (or at its instance) of frequent Commissions of Inquiry or Committees of Public Accounts. One, appointed in 1691, reported that the Regimental Agents refused to show their books. They were, they claimed, the private secretaries of the Colonels, and not public servants. The Commons committed some of them to custody nevertheless; and Colonel Hastings of the 13th Foot was cashiered. In 1697 the Paymaster-General's accounts disclosed that the pay and subsistence of the Army was in arrear to the extent of £2,300,000, and the Commons requested William to appoint persons unconnected with the Army to investigate the cause of the arrears to redress grievances, and to punish groundless complaints. The Commission was not appointed till 1700 and presented its report at the end of 1701.

It reported the utmost difficulty in obtaining access to the books of the Paymaster-General and in examining his clerks. Constant sickness and urgent engagements elsewhere had delayed the inquiry. The Commission found crude misappropriation by means of falsified accounts and forged vouchers. The Commons dismissed the Paymaster-General in 1704, the wrangle having lasted three years . The Chastised officer, Lord Ranelagh, who had the reputation of spending more on houses and gardens than any other man of his time, is commemorated in this familiar London name.

At the Peace of Ryswick in 1697, the House of Commons voted the payment of two weeks subsistence to all other ranks, and to officers half-pay as a retaining fee. This is the first instance of half-pay. It was found later that half-pay was limited to officers serving in English regiments at the time of demobilisation. Officers who had accepted transfers or had been transferred on promotion to Scottish regiments were excluded, and considerable discontent was caused.

Constant petitions for payment of arrears were presented to the Commons. One Colonel, who had distinguished himself in the defence of Londonderry, petitioned for the payment of £1,500 due to him since 1690, and in 1704 he was still petitioning from the Fleet prison, where he was incarcerated for debt, at the very time the Paymaster-General was being dismissed for embezzlement. About 1698 the state of Europe forebode a new war and the Commons voted an establishment of 7,000 for England and Scotland and 12,000 for Ireland (at Irish expense) in addition to 3,000 marines. But service was so unpopular as to make it necessary to offer £3 instead of the usual £1 "1evy-money" for each recruit.

The War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701. The Commander-in- Chief, the Duke of Marlborough, revived many of the best features of the Army of the Commonwealth, and in particular, was obdurate, like other brilliant Commanders, on the necessity of regular pay and good food, clothing and equipment combined with strict discipline as the pre-essential of a successful campaign. Under his aegis, the contractors supplied good bread. The troops received regular pay and were given to understand that they must pay honestly for whatever they took. The Mutiny Act of 1703 for the first time laid down the rates of pay of all other ranks and ordered that subsistence money should be paid weekly, and any balance of pay due every two months; all stoppages, whether by the Paymaster-General or other officials of lesser status, were forbidden; deductions from pay were restricted to clothing on repayment, one day's pay to Chelsea Hospital, and 1/- in the £ to the Queen .

In these reforms Marlborough was assisted by the new 'Controllers of the Accounts of the Army'. In 1705 the Paymaster-General's office was divided, and two Paymaster-Generals were appointed, one for the troops at home, the other for the troops abroad. They were assisted by two Controllers of Accounts, at a salary of £1,500 a year each . At the same time, the Secretary at War ceased to be a private secretary to the Commander-in-Chief, did not proceed with the troops abroad, and became the civilian head of the War Department (later the Secretary of State for War). The Commander-in-Chief was allotted a new private secretary at 10 shillings a day, who accompanied him on service.

Marlborough's reforms extended to the system of clothing. In 1706 abuses were ordered at his instance to be inquired in to by the Secretary at War and General Charles Churchill. The pattern of clothing was fixed; an allowance for clothing was granted; and repayment prices ("offreckonings") laid down. The Colonels of regiments still controlled the issue, but they were themselves controlled by a Board of six General Officers, who sanctioned clothing contracts and after inspection authorised the acceptance of deliveries.

Marlborough attacked also the question of the supply of officers' horses. For each horse £I2 was paid as "levy-money" but losses in Flanders and in transports were heavy and it would appear that officers were not entitled to second or subsequent levy-money. They also paid for transport for their horses at fixed rates . The Duke was instrumental in getting free transport for 26 horses to a Battalion , but when it became known that Irish horses could be obtained as cheaply as £5, the concession was withdrawn.

The Controllers of Accounts soon after their appointment got to work on the Regimental Agents. It was proposed to make them subject to trial by court martial but this project failed, the old argument that they were private secretaries to the Colonels and not public servants prevailing. There is one instance of an agent refusing to pay to the wife of a Lieutenant the allotment made to her by her husband, and only an order by the Queen induced him to pay up.

Officers were burdened with contributions to widows' pensions. In Marlborough's Army in Flanders the contribution was voluntary; but the pension fund was loaded with the cost of pensions of widows who had lost their husbands in previous wars. Elsewhere than in Flanders a fictitious soldier, called the "Widows' Man" was counted in the muster roll of each troop or company, his pay going to the pension fund. After Peter Simple, in Marryat's novel, had searched the ship for Cheeks the Marine, he learned that he was a widow's man! Marlborough disliked the practice, but to relieve his own officers in Flanders he obtained widows' men for some of his regiments. The scale of pension fixed for regulation, varied from £50 a year for a colonel's widow to £16 for that of an ensign. The 5th Dragoon Guards, among others, had to find the pensions of particular individuals, and again Marlborough attempted to get relief for them.

The cost of obtaining recruits often fell very heavily upon officers. "Levy-money" was paid to them but this did not always cover the cost of obtaining recruits, and recruits lost by death, sickness and desertion were a dead loss. Officers serving with the Army in Spain complained bitterly that owing to the excessive mortality on board transports, the actual recruits who arrived had cost £8 to £9 each. The theory was that a recruit was transferred from one officer to another who refunded to the former the cost of raising another recruit; the practice was to pay generally £2 or £3 per recruit to the Colonel who furnished a draft. In 1711 the General Officers recommended that the names of recruits who were lost should be kept on the muster-rolls for the next two musters, in order that pay might be drawn for them for that period, as recoupment for the loss. Sometimes a bounty in addition to the recruit's share of the levy-money was given by the officers, e.g., the Duke of Schomberg offered £2 each to old soldiers to join the Dragoons.

The first Recruiting Act was passed in 1704. The levy-money was fixed at £2 for volunteers, of which half was payable to the recruit. Justices of the Peace were authorised to recruit any able-bodied man who had no visible means of subsistence, the levy-money in this case being £1, divisible between the recruit and the Parish Officer. In 1707 the bounty to the voluntary recruit was increased to £2 for enlistments before the opening of the campaign. Parish Officers who neglected their duty in the enlistment of men of no employment were made subject to a penalty of £10, but their reward was increased to £1 and subsistence at 6d. a day until the recruit was posted to his regiment. In addition, the parish received £3 for every recruit so enlisted. Later the same rewards were paid for voluntary recruits enlisting for three years. This was the origin of the short term of service. The standard of height was 5 ft. 5 ins, below which men were accepted only for the Marines.

These high rates of recruiting rewards gave rise to a considerable amount of fraud. Men were wrongfully deemed to be "of no employment", and bribes were given and taken for their discharge; fraudulent enlistments and desertions were common; the recruit's share of the bounties was not always paid to him; Parish Officers refused to deliver recruits to officers except on payment of excessive charges for their subsistence. A Colonel of the Guards enlisted thieves and debtors for a "consideration", that they might shelter in the Army from the arm of the civil law, and then under threat of discharge or of being shipped off to the wars, extracted further bribes. Such men were known as "faggots" and were neither paid nor clothed and did no duty . On inquiry being made by Parliament it was discovered that a quarter of one regiment consisted of faggots. Frauds, and the cost of obtaining recruits, both to the State and to officers, broke down the whole recruiting system in 1711.

In 1711 the first of the "short service" men became due for discharge. But the situation was unprecedented and the officers had found that these were their best soldiers. The Secretary at War proposed to pass an Act of Parliament to compel them to serve for a further two years, but the Attorney-General advised that they were entitled to their discharge, and on the general ground of encouraging recruiting, they were allowed to go.

Officers were burdened not only with the cost of obtaining drafts for the regiment but also by such things as losses of clothing or the loss of cash (e.g . through shipwreck). To meet these and other charges, it became necessary to build up a fund, and "Regimental Funds" came gradually into existence. When command of a company became vacant, or when a commission became due to be granted, the company or commission might be sold, with the King's permission, and the proceeds put into Regimental Funds.

End of Part 2

Paymaster of the Forces 1661

The

Paymaster of the Forces was a position in the British government. The office, which was established 1661 after the Restoration, was responsible for part of the financing of the British Army. Its full title was Paymaster-General of His Majesty's Forces. This should not be confused with the post of Paymaster General, created in 1836 by the merger of the positions of Paymaster of the Forces, Treasurer of the Navy, Paymaster and Treasurer of Chelsea Hospital and Treasurer of the Ordnance.

The first to hold the office was Sir Stephen Fox.

_by_John_James_Baker.jpg)

Before his time there was no standing army and it had been the custom to appoint Treasurers at War,

ad hoc, for campaigns. Within a generation of the Restoration, the status of the Paymastership began to change. In 1692 the then Paymaster, the Earl of Ranelagh, was made a member of the Privy Council; and thereafter every Paymaster, or when there were two Paymasters at least one of them joined the council if not already a member. From the accession of Queen Anne the Paymaster tended to change with the government. By the 18th century the office had become a political prize and perhaps potentially the most lucrative that a parliamentary career had to offer. Appointments to the office were therefore often made not upon merit alone, but by merit and political affiliation. It was occasionally a cabinet-level post in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and many future prime ministers served as Paymaster.

The duty of the Paymaster was to act as sole domestic banker of the army. He received, mainly from the Exchequer, the sums voted by Parliament for military expenditure. Other sums were also received, for example from the sale of old stores. He disbursed these sums, by his own hands or by Deputy Paymasters; these payments being made under the authority of signed manual warrants as far as related to the ordinary expenses of the army, and under Treasury warrants in the case of extraordinary expenses (the expenses which were unforeseen and unprovided for by Parliament).

During the whole time in which public money was in his hands, from the day of receipt until the issue of his final discharge, the "Quietus of the Pipe Office", his private estate was liable for the money in his hands; and failing the

Quietus this liability remained without limit of time, passing on his death to his legal representatives.

Appointments were made by the Crown by letters patent under the Great Seal. The patent salary was £400 from 1661 to 1680 and 20 shillings a day thereafter, except for the years 1702–07 when it was fixed at 10 shillings a day.

The office of Paymaster of the Forces was abolished in 1836 and superseded with the formation of the post of Paymaster General.

Paymaster of the Forces Abroad

From 1702 to 1714, during the

War of the Spanish Succession, there was a distinct Paymaster of the Forces Abroad, appointed in the same manner as the Paymaster. These were appointed to a special office to oversee the pay of Queen Anne's army in the Low Countries, and are not in the regular succession of Paymasters of the Forces. The salary of the position was 10 shillings a day. Colonel Thomas Moore was paymaster of the land forces in Minorca and in the garrisons of Dunkirk and Gibraltar and is not always counted among the Paymasters of the Forces Abroad.

- Charles Fox (23 December 1702 – 10 May 1705)

- The Hon. James Brydges (10 May 1705 – 4 September 1713)

- Col. Thomas Moore (4 September 1713 – 3 October 1714)