British Expeditionary Force 1940

With The BEF in France by Brigadier L G Hinchliffe MBE

To support the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) which was sent to France on the outbreak of the Second World War there was a carefully prepared increment of the Royal Army Pay Corps. The small cadre of officers was hand picked, and its quality can be judged by the fact that it contained two future Paymasters-in-Chief, Lieutenant Colonel C. N. Bednall and Major O. P. J, Rooney. Due to the virtual non-existence of regular reservists the soldiers, except for the holders of a few key posts, were drawn from the Supplementary Reserve. By the standards of the teeth arms they tended to be elderly and they had little training, except in basic clerical skills. For purely military duties, as distinct from Corps employment, there was a contingent of the King's Own Scottish Borderers.

Two days before the outbreak of war on 3rd September 1939, a key party had been called to the Albany Street Barracks, Regents Park, in London. The bulk of the increment arrived in the next two days, and the mobilisation of the Corps’ Field Force was completed by 5th September. Meantime, the Paymaster-in-Chief of the Force, Colonel (later Brigadier) G. A. C. Ormsby-Johnson, had joined the 1st Echelon of the British Expeditionary Force at Aldershot. With him were him were his Staff Officer, Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier) A. A. Cockburn and his Chief Clerk, SSM (later Major) F. E. Gear. Major (later Colonel) L. H. M. Mackenzie also joined to fill the somewhat nebulous appointment of Field Cashier, Intelligence Duties.

Albany Street Barracks Regents Park

Activities at the Albany Street Barracks went ahead with despatch, despite the fact that the Depot had only been established as recently as March 1939 and represented only a small appendage of the Regimental Paymaster London. Temporary lodgings had to be found for personnel before they moved off to France. This problem was eased by the large exodus of civilians from London due to the belief that air attack was imminent. Work went on round the clock. There were many frustrations such as security restrictions and the black-out. Unlike the nonchalance displayed later in the war, work was suspended each time the air-raid sirens sounded, gas masks were put on, and there was a general exodus to the cellars.

The Units mobilised comprised a Command Pay Office, a Base Clearing House, a Base Cash Office and seven Field Cash Offices. Four of the latter were earmarked for each of the Divisions of the BEF, while the remaining three were assigned to the main ports of entry: Cherbourg, Brest and Nantes. The brunt of the initial work was expected to fall at Cherbourg, which had been selected as the port for personnel. To add to the difficulty, the need for security prevented any currency being exchanged from Sterling into Francs before embarkation.

On the day war was declared the Paymaster-in-Chief at the War Office inspected the Contingent. The following day an advance detail, known as the "destroyer party" left for France. It included Lieutenant Colonel Bednall (who was earmarked to command the Base Clearing House), Major (later Brigadier) R.W. Shaw-Hamilton, the three Port Cashiers and eight NCOs.

During the period 6th to 10th September there was sustained activity at the Albany Street Barracks. The Regimental Pay Office was also busy with its own problems of mobilisation expansion. There was a shortage of transport. Despite problems of collection and assembly space the BEF Contingent managed to get their stores and stationery together. The Medical Officer completed his examination, personnel were documented and donned their brand-new battle-dress. By 11th September the main body was ready for embarkation.

SS Duke of Argyll

Eleven officers and ninety-nine soldiers embarked on the SS "Duke of Argyll" at Southampton on 12

th September and after crossing the water under cover of darkness arrived in Cherbourg the next day.. Despite all the difficulties, not least of which was that each of the component units had been raised from scratch, the speed of the operation had been outstanding in the words of Sir Owen Rooney, writing many years later, “There was a very real sense urgency, unlike later mobilisations during the war”. Morale was high and remained so during the short life of the BEF.

The four Divisional Field Cash Offices joined their formations. Numbers 5 and 7 were located near Brest and Nantes respectively, while number 3, commanded by Major V. W. Rees, assisted by Captain Howell and a soldier increment of only one RASC driver, was left to cope with the exchange problem troops who were flowing through the port of Cherbourg. They succeeded. It was fortunate that Major-Rees, whose career was eventually to include command of the RAPC Training Centre and raise him to the rank of Brigadier, was an officer of resource who, above all else did not stand on ceremony. Everything brought for exchange was dealt with. He accumulated silver and copper coin by the sacksful.

The advance party, after disembarkation, had a ride of 280 kilometres to the assembly area at Le Mans. This was done in decrepit buses, to the accompaniment of air-raid warnings. Having been unable to get any information about the intended locations of the Command Pay Office and the Base Clearing House they went on to Nantes, where they ascertained that premises had been allotted at St Etienne Monlue. Colonel Ormsby-Johnson, who had linked up with the advance party, quickly decided that the premises were useless. It was obvious that those making the allocation of accommodation had no conception of the size and nature or a Command Pay Office. and a Base clearing House. Lieutenant Colonel Bednall needed no prompting to go and find something better, but by this time the main body were well on their way to St Etienne. On arrival in Cherbourg they had waited in the dock area with their stores and equipment, for movement orders. They were still making do with the rations - tea, bully beef and biscuits - which had been issued to cover the journey-from England. No further issues were available.

Security descended like a fog. It was impossible to find out how long the journey to St Etienne would take, or the time of entrainment. Then came orders to load, only to be countermanded when the trucks were half full. The train (designated BB 10) which eventually conveyed them to St Etienne took 25 hours and left the baggage trucks at Nantes in the process! Lessons of self-help were, however, already being learned. Cash had been secured from the Port Cashier in Cherbourg before the train journey started and parties had been out shopping. Officers and soldiers enjoyed French bread, sausages, cheese and vin ordinaire. Only one reservist was disinclined to join in the picnic. He, succumbing to the strain of manhandling crates of stores for which his sedentary clerical life had not prepared him, sprang a hernia. Then, at two in the morning, they were at St Etienne. First they were billeted with villagers gave them a right royal welcome in the village hall in the shape of a first-class meal with wine. Had the buildings in the village been as big as the hearts of its inhabitants nothing could have persuaded the detachment to leave. One major lesson had already been learned. Whenever reconnaissance was to be carried out to earmark buildings for Pay Services use it was essential to make sure that the party included a Corps representative. This had not been done when St Etienne was selected. The result was delay and wasted effort.

Lieutenant Colonel Bednall discovered the local British Commander at the seaside town of La Baule. Also well accommodated in the town were the Headquarters of 2nd Echelon and a British General Hospital. With the Commander's help Lieutenant Colonel Bednall persuaded the French authorities to allot to Pay Services the Casino at Pornichet, an unfashionable suburb of La Baule. It was used as office accommodation and hotels were requisitioned as messes. The officers were located in the "Antoine" and the soldiers in "La Faucille". A fatigue party commenced the job of getting the accommodation into shape. Two days later, on 19th September, the rest of the party arrived, having said a reluctant goodbye to the hospitable folk of St Etienne.

Pornichet Casino 1940

and 2019:

While roulette wheels were being put away, grand pianos shifted and huge windows on the seaward side of the casino and in the roof blacked-out, the task of unpacking stores commenced. Frustration turned to laughter when it was discovered that the first packing cases to be opened contained nothing but eyeshields. Then followed picks, shovels, hurricane lamps and butchering equipment in abundance. There were small pennants and arm bands in profusion. When the stationery was unpacked it proved, in the words of Sir Owen Rooney, to be "of the utmost antiquity". Huge bound cash books and ledgers were produced which had been designed for the South African War. There was virtually nothing of use to the Command Pay Office and the Base Clearing House. Happily, in its palmy days the casino had been furnished for its diverting clerical and financial functions with abundant tables and chairs. Typewriters, adding machines, duplicators and an adequate supply ol' pens, pencils and paper were acquired locally.

Life must have been hard for Pay Services in Pornichet!!

By a quirk of fate, the security screen, which had hitherto hampered both regimental and clerical activity, now came to the aid of both the Command Pay Office and the Clearing House. Neither units nor individuals at large in the BEF knew the location of the Offices. Consequently there was neither mail nor visitors. As a result it was possible to devote the remaining days of September to such matters as improving the lay-out of the two Offices and making sure that the best use was made of the available lighting. The King's Own Scottish Borderers and the Supplementary Reservists worked together with a will. What the latter lacked in youth and training they more than made up by willingness.

Although the majority of the Officers joining the BEF were unaware of it, each of them had a vested interest in the Command Pay Office, as one of its functions was to control their personal allowances. The soldiers of the BEF, on the other hand, had the benefits (not shared by their officers) of the Fixed Centre System. Not only, therefore, was their basic accounting system better, but it was the responsibility of the Regimental Paymasters to ensure that their wives were kept in funds. Each soldier had been issued on leaving the United Kingdom with a Pay Book and the seven Field Cashiers of the BEF kept the imprest holders in the units well supplied with funds. There was, therefore, no shortage of French francs in the soldiers' pockets.

With each pay parade the piles of acquittance rolls became higher. It was the job of the Base-Clearing House to take the rolls off the hands of the Units and send them, with all despatch, to the Regimental Pay Offices in the United Kingdom. But the Clearing House could not commence operations until it was installed in its accommodation at Pornichet. When this had been accomplished the flood of vouchers from units commenced. They could not be immediately transhipped as certain checks had to be made. The ledgers had been redesigned and red tape reduced to a minimum, but agreement with the accounts of the Cashiers and the units had to be ensured. The Reservists were prepared to work day and night, but the strain was heavy and the backlog enormous. While morale remained good the sick parade began to increase. The plain truth was that the staff was only a fraction of the size required, the total reinforcement from the United Kingdom amounting to only eleven soldiers.

By mid-November it was clear that 2nd Echelon, the Base Clearing House and the Officers’ Allowance Section of the Command Pay Office would be better situated in the United Kingdom. This having been agreed with the War Office, the move back was planned for January 1940. In the event 2nd Echelon had left France by 17th December and was in the process of installing itself at Margate. On 3rd January it was joined by the Base Clearing House and the Officers' Allowance Section. A team from the war office (F9) was made aware of the staffing predicament in the Base clearing House, which was corrected in such good measure that billeting became a problem. Shortly afterwards the Clearing House moved to Ilfracombe, where it became the basis of the Central Clearing House which was to serve many operational areas later in the war. All hotels in the town had been commandeered. Three of the most prominent, The Ilfracombe, The Imperial and The Dilkusha were used as Pay Offices, and others for the Pioneer Corps who were also stationed in the town. Some of the better placed and higher classed hotels were used for officers quarters.

Dilkusha Hotel Ilfracombe

The Officers' Allowance Section stayed rather longer until it moved north to become part of the initial cadre of the fixed centre for Officers' Accounts. There were also changes among the cadre of Paymasters in France, Lieutenant Colonel Cockburn had been succeeded as Staff Officer to the Paymaster-in-Chief (BEF) by Lieutenant Colonel W. H. D. Robotham. This officer was selected to command a streamlined Command Pay Office at Rouen, nearer the centre of the BEF area. When originally mobilised at the Depot the Command Paymaster was Colonel (later Brigadier) W. J. H. Bilderbeck. With the departure of the Command Pay Office from Pornichet the first phase of the Royal Army Pay Corps involvement with the BEF was completed'

It had from first to last been a struggle to overcome the inadequacies of pre-war planning - planning in which the Royal Army Pay Corps had been allowed to take little part. Once in a position to do so all ranks in France had shown remarkable resource, from the acquisition of pens and paper to the removal of major parts of the organisation back to the United Kingdom.

In each Command Pay Office throughout the British Army there was, in 1939, a special section dealing with the allowances of the officers within the command. When officers were posted between Commands their accounts were transferred. For those officers who had not opted to have their affairs dealt with by the Army Agents, pay as well as allowances was issued. In this respect the Command Pay Office at Pornichet had the same responsibilities as those in the United Kingdom. Although, by October, most of the officers of the BEF had arrived in France their accounts had not. For this there were a number of reasons. In the case of serving officers the Office holding the accounts would not part with them until firm details of the officers' postings had been published. Security and postal delays made this a slow process. The reservists presented even greater difficulties. For the majority, pay was the responsibility of the Army Agents, but accounts could not become active until recall details had appeared in the London Gazette. Only then could pay commence and allowance forms be sent to officers for completion. Officers were unaware of their personal responsibilities. Nobody, many declared, had told them that they themselves must ensure their families had funds.

From October officers, frequently prompted by letters from home, streamed to Pornichet. The wires to London began to hum. There being no battle casualties, 2nd Echelon allowed their teleprinter service to be used. It was not long before the instruments were transferred from La Baule to the Casino, The basic weakness of the system was fully exposed when it was found that accounts which had been urgently sent to France were, in fact, those of officers in transit to the Middle East. It was, as the days went by, becoming abundantly clear that the conditions of 1939 demanded a Fixed Centre System for officers as they did for soldiers. Thanks to the lull resulting from the "phoney war" it was possible to get on with plans for this in England. Meantime, the staff at Pornichet did what they could to assist officers with their problems - no matter who was responsible.

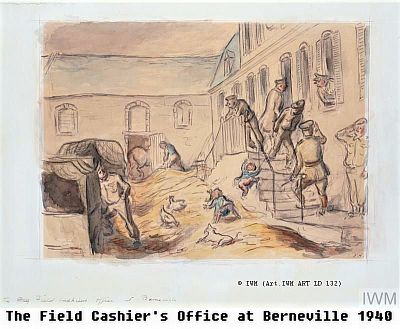

Berneville is near to Arras in France and was on the direct route of the German army thrust in May 1940!

The

Battle of Arras (1940) took place during the Battle of France of the Second World War. It was an Allied counter-attack against the flank of the German army, near the town of Arras, in north-eastern France. The German forces were pushing north towards the channel coast, to trap the Allied forces that had advanced east into Belgium. The counter-attack at Arras was an Allied attempt to cut through the German armoured spearhead and frustrate the German advance. The Anglo-French attack made early gains and panicked some German units but was repulsed after an advance of up to 10 km (6.2 mi) and forced to withdraw after dark, to avoid encirclement.