Army Pay Department and Army Pay Corps in South Africa 1879-1902

Battle of Isandlwana  Click here!

Click here!

Shortage of Paymasters  Click here!

Click here!

Financial Lessons of the African Campaigns Dr J Black  Click here!

Click here!

Proposals of the War Office (Reconstitution) Committee 1904  Click here!

Click here!

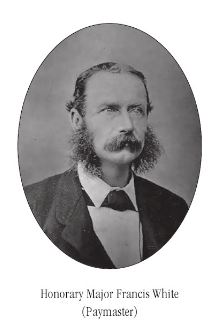

Paymaster Hon Major F F White APD 24th of Foot at the Battle of Isandlwana immediately prior to Rorkes Drift on 22 January 1879.

Francis Freeman White was an officer in the Army Pay Department attached to the 1st Battalion 24th Regiment. He joined the army as an ensign on 15th Feb 1850, promoted to lieutenant on 5th May 1854. He joined the 24th as paymaster on 11th July 1856 and was appointed honorary major on 11th July 1866. Paymasters are not normally expected to fight alongside the rest of the regiment but at Isandhlwana on 22nd Jan 1879, at the age of 49, he had no choice but to fight and die like the rest of them.

Paymaster Francis White's body was found to the left of the 2nd battalion 24th camp. He had apparently been fighting with the companies on the left. The Paymaster-Sergeant George Edward Mead was also killed during this action.

Colonel Mike Snook in his book "How Can Man Die Better: The Secrets of Isandlwana Revealed" describes the action like this:

"The A Company Fight

The indunas of the uMbonambi had rallied their men in the Mpofane Donga to protect them from heavy fire laid down by the 24th during their withdrawal. Now, they judged the time to be right for a renewed assault. Leaping into the open, they whipped up a charge against the front of the camp. The assault came surging in well over a thousand men strong. With only fifty or so rifles available, there was little A Company could do to stop it. Seeing the uMbonambi rushing in from their left, parties of the umCijo leapt to their feet and also pressed an assault against Degacher's men [ed. Captain William Degacher]. The soldiers of A Company realised immediately that they were the focus of the enemy's attention. There was no longer any point in carefully husbanding the cartridges they had left, so they loaded and fired as fast as they could. Although a few dozen men of the uMbonambi were shot down, the regiment's frenzied charge proved remorseless. When the racing warriors got to within a hundred yards, the redcoats looked around for their company commander and ran in to rally around him in a cluster that would pass for a square. In its terrifying isolation, A company steeled itself to make an end. The uMbonambi charged in from all directions, flailing assegais, knobkerries and shields. The momentum of the assault drove the fight back into the 2nd Battalion tents.

No doubt Paymaster White did sterling service with his revolver, but it was in this fight that he fell. Some men rallied again in a small knot just behind the ammunition wagons; they held their ground for a minute or two, until at length their pouches were empty. After a savage and supremely violent flurry of hand-to-hand fighting , this last remnant of A Company was also annihilated."

In the 1st battalion 24th camp the bodies of the slain lay the thickest of all. A determined stand appeared to have been made behind the officers' tents, where lay seventy dead. The body of Colour-Sergeant Wolf, 1st battalion 24th, was recognized, surrounded by twenty of his men. Further down the slope of the hill, about sixty men lay together. Among them were the bodies of Captain Wardell, 1st battalion 24th, and Lieutenant and Adjutant Dyer, 2nd battalion 24th. Quarter- Master Pullen, 1st battalion 24th, was last seen in the 1st battalion 24th camp, where he was encouraging the men to stem the advance of the Zulu's left horn.

But little is really known of the conflict in and around the camp. So swift was the disaster that it is easy to understand that the few survivors should be unable to give any very reliable or consecutive account of the details. The evidence of the dead, as afterwards found and buried where they lay, told the one unvarying tale of groups of men fighting back to back until the last cartridge was spent. Zulu witnesses, after the war, all told the same story : " At first we could make no way against the soldiers, but suddenly they ceased to fire ; then we came round them and threw our spears until we had killed them all."

Lord Chelmsford, the British commander in chief, was with the Natal Native Contingent (NNC) and could scarcely believe the horrible news.

Stunned beyond words, all he could mutter was: “But I left a thousand men to guard the camp.”

[

Top]

A shortage of Paymasters 1884? Questions in the "House"!!

ARMY PAY DEPARTMENT—REGIMENTAL PAYMASTERS.

House of Commons Debate 14 March 1884 vol 285 cc1545-6

1545

MR. ARTHUR O'CONNOR asked the Secretary of State for War, Whether there are at present six Cavalry Regiments, one West India Regiment, and twenty-nine Line Battalions, in which the pay duties are administered by Acting Paymasters or Committees; if he will state the number of Officers of the Army Pay Department who have retired from the Service, but, in consequence of the small number of probationers for the Department, are still employed by the War Office; whether the duties of Chief Paymaster, in the Woolwich and North British Districts, are entrusted to Officers who have so retired; and, whether the Commissariat Department, on its formation, was granted higher rank and pay on account of the great responsibility involved in the charge of the Treasury Chest; and, if so, why the same privileges are not accorded to Officers of the Army Pay Department, to whom are entrusted now these same duties?

SIR ARTHUR HAYTER The Army List will show that there are six Cavalry regiments and 29 battalions which have not Paymasters attached to them; to 13 of these, however, Paymasters have been detailed; but the fact of their having joined has not yet been notified in The Army List. The West India Regiments are allowed one Paymaster only. There are seven officers on the Retired List of the Army Pay Department, who are temporarily employed in consequence of the Department being under its establishment. It may be here mentioned that since the beginning of this year 12 officers have applied to become candidates for the Department. The duties of Chief Paymaster in the Woolwich and North British District are being performed by officers on the Retired List temporarily, only until the arrival home of Chief Paymasters from foreign service. The rank given to the Commissariat Department was not granted with reference to Treasury Chest

1546

duties only, but mainly on account of the other duties for which that Department is responsible. When the Pay Department was formed in 1878, the highest rank in it was that of Major. Since then the ranks of Lieutenant Colonel and Colonel have been given to the officers in charge of the principal stations, and abroad these are the officers who have custody of the Treasury Chest. At the few stations abroad, where an officer of this rank is not serving, the officer in charge is always granted additional pay for the responsibility of the Chest duties.

[Top]

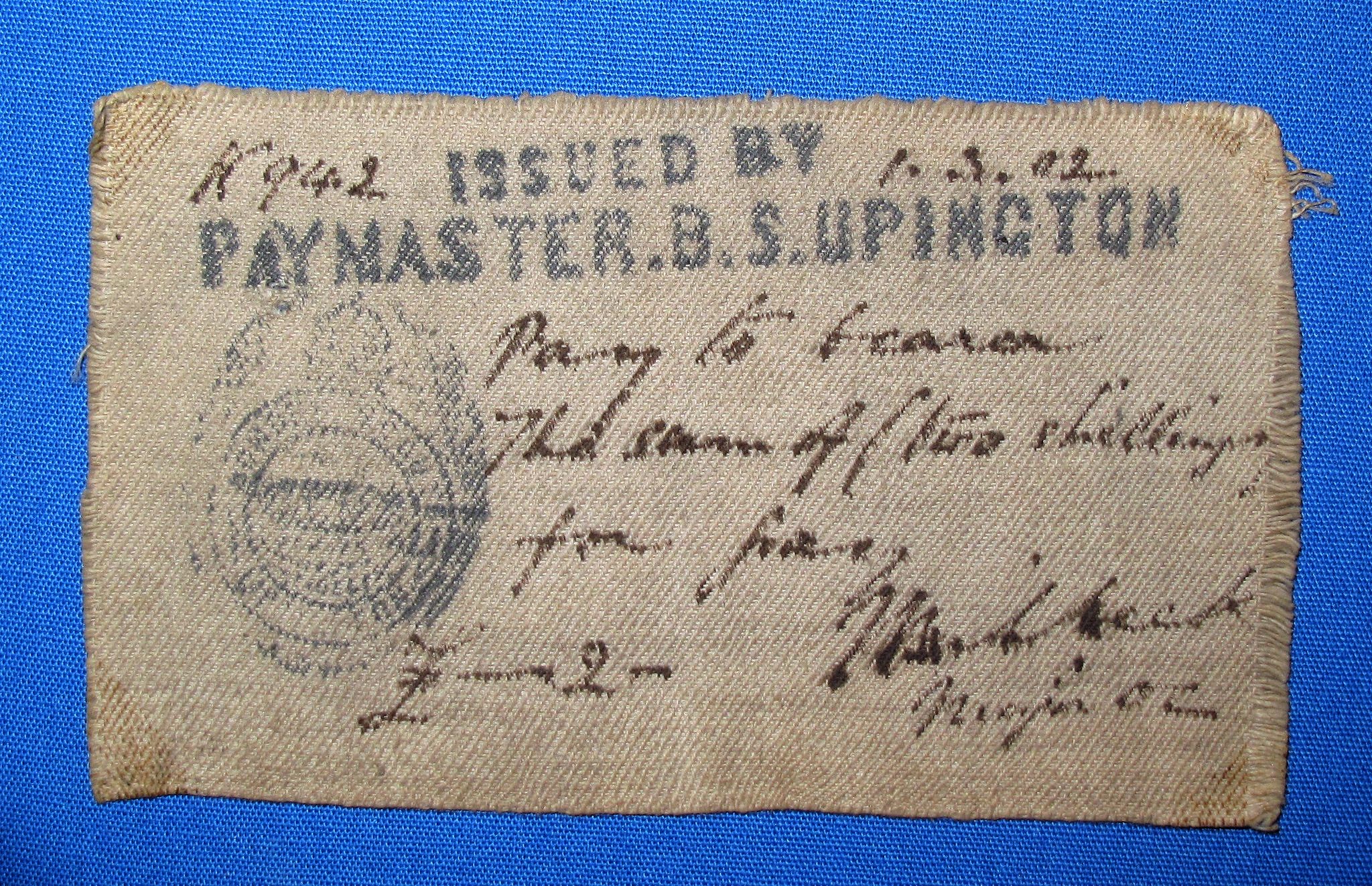

Money order for 2s, made from a shirt during the 2nd Boer War

for the Upington Border Scouts

Currently on display in the AGC Museum

This item is not remarkable in itself but is a clear indication of the problems in Supply and Systems as described in the following article by Dr John Black!

South African Military History Journal Vol 14 No 1 - June 2007

Lieutenant-Colonel Seton Churchill and the financial lessons of the African campaigns, 1879-1902

by J Black

Lieutenant-Colonel Seton Churchill of the Army Pay Department (APD) delivered three lectures at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) between 1895 and 1903, where he identified the existing problems of military administration generally and the inflexibility of the existing system of Army financial administration. Churchill had gained his financial experience in the field during three African campaigns and was critical of the existing system that completely failed during the second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). Army financial organisation and reform are not attractive areas of research by mainstream war historians, and the system of financial structures of the pre-1914 British Army have gone unnoticed within the overall field of military history. Indeed little has been attempted to determine what it cost Britain to have an Empire (Davis & Huttenback, 1987).

Brass cap badge of the Army Pay Corps, worn 1900 to 1901 by warrant officers and non-commissioned officers (SANMMH) .

Two departments

The British Army was small in comparison to the size of the Empire, the Regular Army strength being no more than 105 000 with some 40 000 Reservists. Until 1904 there were two separate wings involved in Army finance. The larger and all civilian Accountant-General's Department had originally been formed in 1855, and was located at Pall Mall, London. The second wing was the all-military APD. However, the APD was small even by comparison with the strength of the Army, numbering no more than 208 officers prior to 1914. The APD had been formed in 1878 from the original Control Department established under the Cardwell Army Reforms in 1871 (The National Archives, WO 32/6268). The larger civilian Accountant-General's Department at the War Office did not accompany the Army within its peacetime garrisons or in the field during operational campaigns. Neither was there any form of transfer of function or personnel between the Accountant-General's Department and the military APD, a criticism noted by Churchill (

RUSI Journal, Vol XLP, 1897, pt 2,1137).

The gulf between the Accountant-General's Department, and the military APD began to expose flaws in the financial system of the Army leading to meltdown during the second Anglo-Boer War. Part of the problem lay in the formation of the APD in 1878 without the actual parameters of responsibility between each of the agencies having been made clear. Also, the work of the APD increased between 1879 and 1890 as the small Victorian Regular Army was called upon to engage in the Imperial wars that were evident in the later part of Victoria's reign, which has some similarity with the contemporary Regular British Army in the first decade of the 21st century. The gulf between the Accountant-General's Department and the APD was a well established fact at the time of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 when the APD suffered its first two casualties - Honorary Major (Paymaster) FF White APD of the 24th Foot, and Lieutenant (Assistant Paymaster) J Hardwick APD.

Lieutenant-Colonel Seton Churchill (1851-1933)

Churchill was born in Dorset, the sixth son of a clergyman. He entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, at the age of 16, and was gazetted as an ensign in the 44th Regiment of Foot (later the 1st Battalion, The Essex Regiment) in 1869. For the next ten years, Churchill served with his regiment in Ireland, India and Burma. He was transferred to the APD as a captain paymaster in 1879, a year after its formation. Churchill became paymaster of the 86th Regiment in India and was part of the reinforcements for South Africa during the closing stages of the Transvaal or first Anglo-Boer War in 1881. Later, during the Egyptian campaigns, Churchill was stationed at the Command Pay Office, Cairo. Promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1895, Churchill was part of the first batch of reinforcements to embark from Southampton for the Anglo-BoerWar in 1899. During this war, Churchill served at the Command Pay Office, Cape Town, and also acted as a field cashier in the Transvaal and Orange Free State. He was medically discharged from the Army in 1902, and settled in Wimbledon. Churchill died, aged 82, in 1933.

Churchill and the financial lessons of the African Campaigns, 1879-1902

As with the Crimean War some forty years earlier, the 2nd Anglo-Boer War exposed major logistical and administrative faults within the structure of the British Army that went beyond the financial deficits. Churchill was appointed as staff paymaster, being mobilised from his peacetime station at the Discharge Depot in Gosport, Hampshire. Thus he was conveniently placed to be mobilised and dispatched with the first batch of reinforcements sent by troopship from nearby Southampton to Cape Town. Churchill took up his duties as a staff paymaster, initially at Cape Town, and then moved into the Cape Colony and the Transvaal, where he became responsible for twenty subordinate paymasters in the field. He returned home and resumed his peacetime appointment at the Discharge Depot, Gosport, until 1902 when he retired due to ill health. The following year, however, Churchill, then in retirement, delivered his third lecture at the RUSI that he called the 'Financial Lessons from the Late War'. In retirement, Churchill's third paper was perhaps more forthright and critical in its analysis of the military financial system that had collapsed during the 2nd Anglo-Boer War than it might have been had he still been in service. Indeed Churchill's third paper appeared as the fulfillment of the prophecies he had expounded in the first two papers delivered in 1895 and 1897 respectively.

The introduction of Churchill's third paper began with a resume of his APD career from 1880. It is interesting to note the increased bureaucracy that occurred during the period 1880 to 1895. Churchill explained that, in 1880, his duties had not been onerous, commenting that 'I had one clerk, and if I received half a dozen letters in a day on an average, it was not outside my work; and probably the payments for about 800 men did not exceed £28 000 per annum' (Churchill, 1903: 285,

RUSI Journal, Vol XLVII, pt 1).

At that time, military clerks came from regimental sources and not from the APD. However, a decade later, from 1890, the volume of work had increased for reasons previously described. This necessitated the establishment of a corps of military clerks to support the financial administration within the station pay offices. Thus, in 1892, the War Office sanctioned the establishment of the Army Pay Corps (APC) to act as clerks to the APD. The ranks of the APC were made up of noncommissioned officers and warrant officers, most of whom had previously served either with the Corps of Staff Clerks or had been military clerks within other branches of the Army.

In his three papers, Churchill's criticisms of the system of Army finance pinpointed one major flaw in the system - that there were two systems of Army finance, one for peace and the other for foreign service, including war. This state of affairs had developed unintentionally due to the existence of the two financial arms within the Army. Each had its own customs and internal methods of operations and priorities. The financial system for the Accountant-General's Department was for peace, the APD for foreign service and war. Churchill explained that 'instead of training officers and men, during the many years of peace for the requirements of war, we have to try and unlearn much of the past, and to start a new system for war, as our financial system is orientated by civilians who are not personally acquainted by the stern realities of war' (Churchill, 1903: 281,

RUSI Journal, Vol 1, XLVII, pt 1).

Churchill gave two practical examples of the implications of running two financial systems that he had experienced first whilst serving as a staff paymaster at the Central Pay Office, Cairo, during the Egyptian campaigns, and later during the 2nd AngloBoer War: 'Just to give an example from among many:

In Financial Instructions for 1899, the year in which war broke out, Paragraph 144 sanctions the paymaster of all claims under £1 000 at home, but directs that all claims over the amount be sent to the War Office. But on foreign service as well as on active service, there is no limit to the amount of the claim that may be made without reference to the War Office. As a young major in the Egyptian Campaign, I had to pay many contractor bills, one of which I remember amounted to £35 000, and in the recent South African campaign, I observed from my cash book that cheques as large as £166 000, £94 000, etc, were issued showing how on active service all the ridiculous instructions of the War Office have to be set on one side. Yet in peacetime a full colonel in the Army Pay Department could not pay a contractor's bill of over £1 000! How are officers and clerks to be trained for foreign service and for the responsibilities of war, and the checking of contractors' claims, if they are denied during peacetime at home the education that is required by dealing in large figures?' (Churchill, 1903: 281,

RUSI Journal, Vol XLVII, Pt 1).

In 1899, both the APD and APC were small in comparison to the overall Regular Army. The total strength at home and abroad was 206 commissioned APD paymasters and 650 APC clerks of all ranks, most of whom were located in pay stations based in the United Kingdom with a staff of only five or six in total. Previously, in his 1897 lecture, Churchill had raised the practical difficulties of mobilising the APD from the small scale of pay stations within the UK that could be drained of staff in time of emergency. Prophetically, his concern became acute two years later, during the mobilisation of the APD and APC staff for operational duties during the 2nd AngloBoer War.

Churchill's practical experiences reflected the fact that the system of Army financial structures did in fact collapse as he had foreseen in his 1895 and 1897 RUSI lectures. In order to bring the APD and APC up to strength in South Africa, the station pay offices were emptied of staff. This was conducted without any advice from senior military financial staff, the action being carried out under the direction of the Financial Secretary to the War Office on advice given by the Accountant-General, whose staff never strayed into active operational areas. There was no executive military financial adviser with field experience to give such advice.

The Indian Army model

The model identified by Churchill as the way forward in the British system was to be found in the Indian Army Military Accounts Department. All military finance in India, from the humblest clerk to the Auditor-General to the Viceroy, was conducted by the Military Accounts Department. During the 2nd Anglo-Boer War, Churchill had witnessed officers of the Indian Military Accounts Department, who, though inferior in rank to their British APD counterpart, had more authority over financial matters. 'If we turn aside for a moment to India we see a pleasing contrast to our English financial system. In South Africa there were a large number of officers and natives lent by India. In order to arrange for their payment, an officer of the Indian Military Accounts Department was sent, and though a comparatively junior officer, with much less experience, he had absolute powers of controlling expenditure and giving decisions on knotty questions that might occur. The question arises, why should not the War Office have treated their selected officer with the same confidence that the Indian Governments showed to their representative?' (Churchill, 1903: 280,

RUSI Journal, Vol 1 , XLVII, Pt 1).

Civilian versus military expertise

Particularly in his 1897 lecture, Churchill reinforces previous arguments that, in matters of military finance, the Secretary of State for War, the Under-Secretary of State for War and the Financial Secretary were advised by civilians and not by military specialists. Churchill made the point that the civilians at the War Office, although well versed in detail about procedure, never left Pall Mall and had very little first-hand experience of how the system worked in the field on an operational basis whereas the 'existing system is that 208 officers of the Army Pay Department do all the executive financial work abroad and at home, get all the hardships and the bad climates, the campaigning and dull stations, but none of the plums!' (Churchill, 1897: 1136,

RUSI , Vol XLI, pt 2).

The dual system of financial services to the Army in the field completely broke down during the first weeks of the war in South Africa. There was no concrete plan for the administration of the financial services within the order of battle for the British Army. A command pay office was established at Cape Town and field paymasters were seconded to field force headquarters. Due to the inadequacies of Financial Instructions for the Army issued by the War Office in Pall Mall, most paymasters in the field had to interpret these regulations as they saw fit in their individual situation. However, the actual payment of the Army in the field was left to the regimental company commander (normally a captain) and the company colour sergeant. Due to 'a shortage of acquittance rolls and paylists (owing mainly to the scattering of companies of regiments within the Cape Colony and the Orange Free State), the company commanders and field paymasters had to improvise.

Major Claude Bray APD, (later Major-General, who was appointed Paymaster-in-Chief to the British Expeditionary Force for the duration of the First World War) spent the 2nd Anglo-Boer War at the Command Pay Office in Cape Town where he was in charge of the audit of the paylists and other accounts submitted by regiments from Britain and her colonial allies. Bray gave evidence to the Clayton Committee set up in 1903 to assess the reason for the collapse of the financial system during the war, and duly reported to the Committee that, 'it is not to be wondered at that a system, which even during peace was only carried on with difficulty, should have in time of war broken down. How could it be expected that an Officer commanding a Company, which for months together was continually on the "trek", could sit down with a Colour Sergeant on the veldt, with a biscuit box for a table and an indelible pencil for a pen, and compile a pay list with its supporting vouchers? In many instances during the present war all Company records and documents have been captured and destroyed by the enemy, pay lists and vouchers have been lost in the post, company officers and Pay Sergeants have been killed and wounded. It is not surprising that accounts cannot be rendered and thousands of non-commissioned officers and men remain unsettled with, and never likely to be settled with, without great loss to the public. (Quoted from Hinchliffe, 1983, p 42).

Churchill also recounted his experiences as a senior APD officer and staff paymaster, South Africa, in 1899 when his responsibilities included soldiers from Dominion and Colonial forces: 'During the recent war I had at one time to pay about 1 500 officers and 30 000 men of the Colonial Forces, scattered all over South Africa, and was in communication with eleven different Colonial Governments. The actual payments amount to about two million in twelve months. In addition I had 112 commanding officers to whom I had to give the minutest instruction, besides about 20 paymasters. Yet, in spite of all this addition of work - which I venture to think was quite equal to that of any staff officer - I was still called by the old name of "paymaster".' (Churchill, 1903: 285;

RUSI Journal, V1 , XLVII, pt 1).

According to Churchill, the number of APD officers available for operational duty in South Africa in 1899 was 60, supported by 180 APC clerks. This number was hardly sufficient to support the size of the armies from the Empire being sent to the Cape. In addition, there was an acute shortage of clerical staff and personnel versed in financial administration required to administer and support the armies in the field. Churchill had recommended the temporary employment of unemployed clerical staff from the Rand goldfields, most of whom were British, where the mines and supporting commercial institutions had closed as a consequence of the outbreak of the war. This recommendation was put into place and temporary civilian staff were recruited for duties with APD establishments. Churchill recounted this experience in his third lecture in 1903, when he explained that there was an 'enormous number of civilian clerks from Johannesburg who were only too glad to get some employment. This was a piece of good fortune - which really saved the situation. Many of these clerks were good men from banks and thoroughly well trained accountants. Of course they were very costly, many getting as much as 10 shillings per diem. In no future war could we ever count on having an enormous number of English refugees on the spot to help. In spite of their ability however, we found how utterly unable they were, from a want of knowledge of our regulations, to do the work that our well trained clerks on half their salary could do. They saved the situation for that occasion, but for the credit of our Service, it is hoped that we shall never again be put into such a position.' (Churchill, 1903: 419,

RUSI Journal, Vol 1 , XLVII, Pt 2).

However, Churchill was wrong in his forecast for the future regarding civilian temporary staff. Just eleven years later, in September 1914, the War Office had to call on the services of civilian accountants, bankers, commercial managers and those with clerical expertise, to become temporary acting civilian paymasters or specially enlisted clerks to assist with the work in the UK-based regimental and command pay offices (Black, 2006, pp 260-80).

Conclusion The aftermath of the 2nd Anglo-Boer War left the British psyche in a state of flux. The war had been difficult for a supposedly modern British Army that had initially suffered reverses inflicted by a volunteer army that was considered at the time to be only a militia of Boer farmers. Unfortunately for the complacent British, they had not learnt from the recent history of the Transvaal, or 1st Anglo-Boer War, 1880-1. The later episodes of the 1899-1902 War included guerilla action by the Boers and a British 'scorched earth' policy and concentration of civilians who, it was presumed, might give aid to the Boer commando forces. There were numerous enquiries aimed at certain failures that were exposed in the South African War. These included Royal Commissions, chaired by Lord Eglin, established to enquire into the military preparations and other factors associated with the 2nd Anglo-Boer War (Cd 1789, 1904a; Cd 154, 1904b; Cd 1790, 1904c). Another contemporary Royal Commission was established to investigate war stores in South Africa, as there had been cases of neglect and fraud associated with such stores and ordnance during the course of the war. Unusual for the day, this particular report included a specialist opinion from a firm of chartered accountants, Messrs Annan, Kirby, Dexter & Co (Cd 3130, LVIII: 1906, pp 1-73).

On his retirement in 1902, Churchill resided at Wimbledon. During his military service he was renowned as a strong churchman and, whilst in the Army, he had written a number of moral tracts, including

Betting and Gambling, published in 1894 on the evils of gaming, and Forbidden Fruit for Young Men (1909), and a biography, General Gordon, published in 1906. Whilst in the APD, Churchill was elected as a member of the Church Missionary Society and was also elected to both the House of Laymen and the Representative Church Council in 1895. His obituary, in the Wimbledon Borough News, 24 March 1933, commented that Churchill 'was a man of strong religious views, founded the Lichfield Soldiers Home in 1890'. During the First World War, he undertook voluntary work in recruiting for the Army. On his death in 1933, he was afforded a short obituary in the Times newspaper, 22 March 1933, in which was stated that he also wrote 'on the moral dangers which beset boys and young men'. Churchill was elected to the Wimbledon Borough Council in 1912 and to the Surrey County Council from 1913 until 1919 (Wimbledon Borough News, 24 March 1933).

The military writings and experiences of Lt-Col Seton Churchill remain important today because the financial cost and accountability of war is still a neglected topic in any study of warfare as is the cost of maintaining the British Empire, a point made at the beginning of this paper. The experiences of the APD during the era of the small wars of the late Victorian era, including the African campaigns, also emphasise that being a paymaster in the Victorian British Army was by no means a boring and easy life, and that none of the plums came with the office.

Bibliography Black, J, 'Supermen and Superwomen: The Army Pay Services during the First World War' in Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Autumn 2006, Vol 84, No 339, pp 260-80.

Churchill, Seton, Major, 'Army Financial Reform, Part 1', in

RUSI Journal, 1895, Part 1, Vol XL, pp 36-46.

Churchill, Seton, Lt-Col, 'The defects in our military financial system, Part II', in

RUSI Journal, 1897, Vol XLI, pp 1 134-55.

Churchill Seton, Lt-Col, 'Financial lessons from the late war, Part I' in

RUSI Journal, 1903, Vol XLVII, pp 278-88.

Churchill Seton, Lt-Col, 'Financial lessons from the late war, Part II' in

RUSI Journal, 1903, Vol XLVII, pp 418-32.

Churchill, Seton, Lt-Col,

Forbidden Fruit for Young Men, 7th Edition (James Nisbett and Co, London, 1907).

Davis, Lance E & Huttenback, Robert A,

Mammon and the Pursuit of Empire: The Political Economy of British Imperialism, 1860-1912 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987).

Hinchliffe, L G,

'Trust and be Trusted' - The Royal Army Pay Corps and its origins (Published privately by the Corps Headquarters, RAPC, Worthy Down, Winchester, Hants, 1983).

O'Mallay, L S S,

The Indian Civil Service, 1601-1930 (John Murray, London, 1931).

Packenham, T,

The Boer War (Weidenfeld. and Nicholson, London, 1979) .

Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the civil and professional administration of the Navy and Military Departments and the relation of those departments to each other and to the Treasury (Hartington Commission), British Parliamentary Papers (Cd 5979) XIX, Report with Appendices, 1890.

Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the . military preparations and other matters connected with the War in South Africa (Eglin Commission), British Parliamentary Papers (Cd 1789), Vol XL, 1904a.

Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the : military preparations and other matters connected with the War in South Africa (Eglin Commission), British Parliamentary Papers (Cd 154), Vol XLI, 1904b.

Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the military preparations and other matters connected with the War in South Africa (Eglin Commission) British Parliamentary Papers (Cd1790) Vol XL, 'Minutes of Evidence'.

Royal Commission on War Stores in South Africa, British Parl.. Papers (Cd 3130) LVIII, 1906.

The Times, 22 March 1933 and 28 August 1934.

The Wimbledon Borough News, 24 March 1933.

War Office (Reconstitution) Committee (Esher Committee), British Parliamentary Papers: Part 1 (Cd 1932) VIII; Part II (Cd 1968) VIII; Part III (Cd 2002) 1904.

The National Archives Library Kew, London:

The Army List, 1870 to 1920.

The War Office Staff List, 1870 to 1920.

WO 32/6268, 'Reorganisation of the Control/SubControl Department and formation of the APD'.

The Regimental Secretary, Royal Army Pay Corps Association, Adjutant-General's Corps Centre, Worthy Down, Winchester, Hants, S02 14F:

Ledger RS 83901 Records of Service APD Officers, 1850-1878.

Ledger RS 83902 Records of Services APD Officers, 1879-1914.

[Top]

War Office (Reconstitution) Committee. Published London,H.M.S.O.,1904.

"We desire to repeat that the criticism of military policy by civilians, whose functions should be limited to examination of estimated cost and expenditure, has become a habit, incurable unless drastic reforms are applied.

Our proposals under this head resolve themselves into-—

(a) A complete redistribution of financial work and responsibility.

(b) Further decentralization of accounting and financial assistance under the military chiefs.

(c) Separation of army accounts and army finance.

(d) The creation of a consolidated and homogeneous body, trained in accounting work, to replace the present dual system.

(e) A large simplification and reduction of Regulations.

(f) A change of personnel, in order to mark emphatically a complete change of system.

To the last-named proposal (f), we attach the greatest importance, as nothing which we can suggest will so fully convince the rank and file of the Finance Branch that the old system must be abandoned, and completely new habits formed."

[Top]