Notes on Army Pay 1711 to 1802

Notes on the History of Army Pay

By LIEUT-COL. E . E. E. TODD, O.B.E, R.A.P.C.

In order to understand the tortuous system of financing the Army in the eighteenth century, It should be remembered that Parliament had never reconciled itself to the existence of a standing Army. On occasion even the annual Mutiny Act, by which alone military discipline could be enforced and without which crimes could strictly be dealt with only under the civil law, was not renewed.

The recognised national army was the Militia, and the Standing Army was regarded still as more or less the King's personal responsibility. Regiments were intended to be as self-supporting as possible and any proposal to make the State shoulder their burdens was looked at askance. As funds could not be provided from the Exchequer, it was necessary to adopt a number of curious expedients, such as the "Widows' Man" to provide for necessary services. An illuminating insight into this, from to-day's point of view, perverse attitude, is given when Marlborough fell from power.

In 17II the Duke was himself charged by the House of Commons with embezzlement, on the ground that he had been in receipt of commission from the bread contractors, amounting in all to £63,000. Marlborough gave evidence that these commissions had regularly been received by Commanders-in-Chief to form a secret service fund; and he volunteered that in addition and for the same object, he had taken 21 per cent. of the pay of the troops serving abroad. The House dismissed him from his command and instructed the Attorney-General to prosecute. The Duke of Ormonde was then appointed his successor, and was authorised to receive the very same commissions, and for the same object, as Marlborough was indicted for. It was contrary to the public or financial policy of the time to vote a sum directly to meet the cost of Secret Service.

John Churchill 1st Duke of Marlborough

As Marlborough's power declined, so the old abuses which he had done so much to correct, crept in once more. In 1712, as the result of the bread scandal, new contracts were entered into and bad bread was supplied. The consequent discontent among the troops was fanned by the rumour that arrears of pay on the conclusion of peace would, as previously, be withheld. Three thousand men abroad mutinied, demanding good bread and payment of arrears. Ten of them were court-martialled and shot.

The forces which suffered most from arrears of pay and other abuses were the Marines and troops in the Colonies. A rigid rule was that to receive pay a Regiment must be mustered. As the marines were scattered throughout various ships and ports, they could seldom be mustered and were consequently seldom paid. There is one instance of a regiment of marines not having received pay for eight years. Sometimes this state of affairs was due to or aggravated by, the corruption of the Commissaries of the Muster. The Commissary at Portsmouth is described as "a superannuated old man who was rolled about in a wheel-barrow". An attempt to bring relief to the Marines was made in 1748 by transferring them from the jurisdiction of the War Department to that of the Lord High Admiral.

Service in the Colonies was dreaded more or less as a penal sentence. Recruits were closely herded on board the transports, sometimes for months at a time, largely to prevent desertion and epidemics of disease invariably broke out. A Guardsman of the time describes life on a troopship as "continual destruction in the foretop, the pox above board, the plague between decks, hell in the forecastle and the devil at the helm". There was no system of relief of foreign garrisons, and regiments were frequently stationed in the Colonies, as at Gibraltar, for as long as 20 to 30 years at a time. Garrisons in distinct colonies, as in the West Indies, were for all practical purposes, lost to sight and mind. No regular provision was made for pay and one Irish regiment in Jamaica received no clothing for two years. Their officers, when efficient, made what shift they could out of their own or borrowed money; others left the regiments to look after themselves and came home. A tropical station under such conditions, without either knowledge of or means to deal with epidemics of fever or dysentery was not a pleasure resort.

Throughout the eighteenth century a complex system of army accounting grew up, and at last was killed by its own complexity. The Paymaster-General used to present his Estimates to the Treasury, who made a lump sum payment into his account at the Bank. The Paymaster-General issued cash as required to the Regimental Agent (who was the Colonel 's private clerk) ; he in turn Issued to the Regimental Paymaster (then an Officer nominated by the colonel to carry out pay duties in addition to his military duty) ; and the RP made issue to the Captains of troops and companies. The Captains accounted to the Regimental Paymaster; he in turn to the Agent; and the Agent to the Secretary at War. When the Secretary at War had accepted the accounts of all the Agents, the Paymaster-General refunded any balance due to the Treasury. Hence every delay in issuing cash to the Agent, and every delay of the accounts on their laborious way to the Secretary at War, meant the greater amount lying at the credit of the Paymaster-General. The interest thereon was regarded, not as public funds, but as the personal perquisite of the Paymaster.

During the period 1757-65 the average yearly balance held by Lord Holland was £455,000; from 1766-75 Mr Rigby held an average of about the same; and the accounts of neither had been finally passed by 1781, that for five years or more two ex-Paymasters were living on the interest of nearly a million pounds of public money. It was established that £413,000 Issued in 1720 had never been accounted for at all.

The Treasury drew up the "Establishment" of the Army under five Heads, of which the first was the pay of all ranks and the others were allowances for Widows, Colonels, Captains and Agents respectively. The allowance for Widows consisted of the full pay of two fictitious men per troop or company. As has already been pointed out according to the financial principles of the time, the House of Commons was not asked to vote a direct sum for the provision of pensions; It could be asked only to vote the pay of the Army, and an accepted fiction grew up that two soldiers were being paid when everybody knew that they did not exist; and so in time certain classes of expenditure were always calculated in terms of these fictitious units. The Widows' Fund was held by the "Paymaster of Widows' Pensions", whose outstanding balance ranged from £24,000 to £65,000, on which he drew the interest, and, to whom each widow paid a fee of two guineas on first drawing her pension plus an annual fee of six shillings.

The allowances for Colonels consisted of the subsistence of one fictitious man plus the gross off-reckoning of four fictitious men. The meaning of the terms "subsistence" and "off-reckonings" will appear later.

The allowances for Captains consisted of the subsistence of two fictitious men. This formed a fund to meet expenses of recruiting, and the Agent credited it to a Fund for this purpose; called the "non-effective fund" in the Infantry and the "stock-purse" in the Cavalry.

Finally, the allowance to the Agent consisted of the subsistence of one fictitious man. In addition to this, as will be seen, the Agent got a commission on the pay of the Regiment.

The pay of the Army, which was the first of the Treasury Headings, was shown in the Regimental accounts when finally drawn up, under the headings of Poundage, Contribution to Chelsea Hospital, Subsistence, Off-reckonings, Clearings and Respites. To deal with the simplest first, Respites included all pay which had been forfeited. The contribution to Chelsea was one day's full pay of all ranks. Poundage was the time-honoured deduction of 1/- in the £ from the pay of all ranks. Out of this was paid a further sum to Chelsea Hospital, the salaries of the Paymaster-General and other officials, various exchequer fees and finally "return-poundage" i.e., the refund of poundage in certain circumstances. Off-reckonings included stoppages for clothing, etc., and this heading alone called for the whole-time services of one Paymaster in the P.M.G.’s office. Subsistence was the proportion of the soldier's pay that was left after the deduction of off-reckonings, poundage, etc. This was supposed to be 6d. a day for an infantry private; but the last heading, "Clearings", included stoppages from Officers similar to the off-reckonings of soldiers, also 2d in the £ on the gross pay of the regiment for the benefit of the Agent, also the amusing composite item, of so much of the soldier's subsistence as had not been issued under the name of subsistence.

Such was the state of affairs as reported by the Commission of Accounts of 1781. This chaos of accounts became entrenched throughout the 18th century; and the Commission for all practical purposes found no witness who could fully explain them, gave up the attempt to understand them as a waste of time, reported that not one individual in the Army received the pay that was assigned to him by the law of the land, that nobody knew whether or not he had received all that was due to him, and proceeded to introduce reforms without investigating the system further, Before proceeding to deal with these reforms it is necessary to mention the main cause which led up to the appointment of the Commission and to realise that it was largely considerations affecting the pay of the Army that brought about the next period of progress. After the Seven Years War, no man entitled to his discharge could be persuaded to re-engage. After the next war, that of American Independence, a bounty of 1½ guineas was offered for re-enlistment, but without effect. The Royal Scots, to take one example, lost 500 out of 700 men. The middle of the 18th century saw a rise in the general standard of comfort of the nation; and the pay of the soldier did not rise in proportion. Not only did the pay not rise, but the conglomeration of stoppages was out of all reason. It took a long time before the lesson was learnt-that the soldier's standard of comfort must, at least in a voluntary Army, be in accordance with that of corresponding ranks in civil life.

The reforms of the commission went only a short way in this direction. The Secretary at War was made responsible for all Army expenditure. The Army Votes were consolidated under five heads-Pay, Clothing, Agency, Allowances and Recruiting. A special Act of Parliament was passed to control the Office of the Paymaster-General, and the chaos of accounts and commissions on pay was reduced. One error almost certainly was made - the appointment of Commander-in-Chief lapsed in 1784. This left the control of the Army in the hands of the Secretary at War, who was a politician, and there was nobody of sufficient standing to force upon Ministers the necessities of the Army. The necessities would not be denied, and further reforms were necessary, but were attained only after bitter experience. Looking back, it seems strange that the reforms were not altogether popular in the Army. The great Edmund Burke took a hand in the work in Parliament, and when he abolished "non-effective accounts" and' "stock-purses", the Adjutant-General talked of "Mr. Burke's infernal Bill," whilst admitting that these fund's lent themselves to what he called "manoeuvre".

What the Commission did not do was to increase the pay of the Army. Another fifteen years and a mutiny was required before any substantial increase took place. In the meantime it became more and more difficult to raise recruits, and desertions rose to immense proportions. It used to be the custom to send round recruiting parties in the spring only; from 1785 annual circulars ordered them to work in summer and autumn also, and impressed on the Colonel the necessity of increasing the number of recruits. Permission was given to take prisoners serving time in gaol, seamen who had been thrown out of the Navy and even out-pensioners of Chelsea. Directions were issued to recruit in Ireland as recruiting was practically useless in England. The 60th, or Royal North Americans, who were stationed quasi-permanently in the West Indies paid 7 guineas for soldiers from the Continent of Europe. In 1798 the bounty to recruits was fixed at 3 guineas, with a further 2 guineas to the Recruiting Officer; but this was not enough; and the Adjutant-General wrote: “the whole country is overrun with Recruiting Officers and their crimps; and the price of men has risen to fifteen guineas a head at least". General Luttrell proposed that men for the Infantry should be enlisted in the first place for seven years, whereon they could re-engage for another seven years with half the recruiting bounty and a guinea a year to be paid at the end of fourteen years; and then reengage for a further seven years, receiving their 7 guineas on re-engagement, and being promised a Chelsea pension at the end of 21 years. This was not adopted, but is quoted here because of its similarity to a service system now in vogue.

Under the stress of the War of the French Revolution, expedient after expedient was tried in order to swell the ranks, One of the most curious was the promotion of Officers in proportion to the number of recruits the Officer might raise, in this game Officers' wives took a hand and wives at home speculated in recruiting while their husbands were abroad at the wars, Lady Sarah Lennox wrote to a friend: “Think of my bad luck about recruits. If I had seen an Officer one fortnight sooner who is here, he would have sold me 20 at 11 guineas per man. Is not that unfortunate; but they are now, gone". And to another friend she wrote :- "Is there any chance of recruiting men of 5ft.4ins. for 10 gns. and as much under as possible, in your neighbourhood?".

In 1793 a Lieutenant advertised in the London paper for 10 recruits, to be passed at Chatham wlthin six weeks. The reward offered was 2,000 guineas. In the same year the recruiting bounty was raised to 10 guineas. In the following year contracts were entered into for the supply of recruits at 20 guineas. Two years later an Act was passed to transfer 10,000 militiamen to the regular forces on payment of a bounty of £10, but it was a dead letter owing to the opposition of the Lords Lieutenants. The militia was financed out of the Land Tax, which naturally was paid by the large landholders. The militia in consequence was regarded as the peculiar property of the country gentlemen, and the Lords Lieutenants of the counties often spent large amounts on it out of their own pockets. Within two years, however, the opposition was broken down, and then entire Companies or even Battalions of militia were enlisted in, the Regulars. In the year 1800, one, Ensign Nugent, was given a contract to provide 1,000 men and 500 boys, at £24 a man If enlisted in Ireland, £21 in England, and £21 a boy in England or £ 18 15s. in Ireland, The error was, of course, to pay so much for enlistment, and so little for service; so that alternate enlistment desertion and re-enlistment became a profitable speculation, albeit a speculation with great attendant risks.

In Ireland one out of every six soldiers on the establishment deserted every year. Deserter depots were opened at Cork and Dublin, for the reception and embarkation of deserters who had been sentenced to perpetual service abroad. The largest known batch was 122 deserters shipped to join the 60th in the West Indies, yet the 60th performed some of the finest fighting service of any regiment. Death sentences on deserters were not uncommon, and it was announced on behalf of the King that he would confirm all such sentences. The Army Chiefs, but not the Ministers (for in the absence of a Commander-in-Chief there was no one to impress the facts upon them) well knew the basis of the trouble. Having in mind the low rate of pay, the Adjutant-General said: "Unable even to satisfy the common calls of hunger, and being without hope of relief, the soldier naturally deserted in despair".

In the Adjutant-General's opinion, the subalterns were even worse off than the privates. In 1786 the Cavalry Colonels in Ireland represented that the entire pay of a subaltern of Dragoons was not enough to maintain his horse and servant. Two years later, the Adjutant-General wrote: "The addition of a shilling a day to the subaltern's pay will, I fear, seem too considerable to the Government to grant, but something must be done for both privates and subalterns."Yet at this time, the Government had a standing arrangement for 12000 Hessians to be ready for service under the British flag, in return for an annual subsidy of £36,000 a year.

In 1792 a new Pay Warrant was issued by which poundage was abolished, stoppages were lightened, and a bread allowance of 10½d. per week was added. Even then, the actual cash payments to the infantry private, after stoppages for clothing, necessaries and food was 18s. 10½d. per year, payable every two months. Within two weeks the Adjutant-General reported that it was easier to get recruits and that desertions had decreased.

The official pay of the Infantry privates was, as it had been since the days of Queen Mary, 8d. per day. Of this 2d. was deducted automatically for ordinary clothing; food was deducted at 3/- a week; and necessaries cost £3 5s. 5d. a year. These necessaries which the soldier had to provide out of his pay were as follows :- One pair of gaiters; two pairs of gloves; the repair of shoes; one pair of stockings; two shirts; foraging cap; knapsack (once in six years) ; pipeclay; whiting; clothes-brush (once in four years) ; three shoe-brushes; black-ball ; worsted mitts; powder-bag and puff (once in three years); two combs; grease and powder for hair; washing at 4d. per week. In addition the soldier was supplied at the public charge with the following:- One pair of gaiters; one pair of breeches; the repair of clothes; one hair-leather ; his share of watch-coats, worm and musket-tools (every five years); emery and brickdust and oil; the whole of which was valued at 16s. 11½d. per year.

Reforms, whether of minor or major importance, succeeded each other during the next few years. Alterations to clothing, and the cost of horse-clothing in the Cavalry, were made a charge on public instead of regimental funds. The provision of the horse itself was still a personal matter for the Officer; the price had risen ten-told since we last heard of horses being bought in Ireland for £5; and an order was issued instructing the Colonels to purchase horses at a price not over £50 for any Officer who had not provided himself with one. Of the utmost importance was the creation by Pitt in 1794 of a Secretary of State for War, who four years later became the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. The office of Commander-in-Chief was revived. The Secretary at War continued to exist, but was confined to financial responsibility for both the new Secretary of State and the new C. in C. He continued nevertheless to exercise a strong influence on policy. A Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for War also appeared.

In 1797 an additional Officer was added to the establishment of each Regiment as Paymaster. Hitherto the Paymaster had done his ordinary duty in addition to pay work. The new Paymaster was still appointed by the Colonel - the Colonel being still personally almost the proprietor of his regiment. Then arose direct correspondence between the Regimental Paymaster and the Secretary at War on financial matters, over which the personal control of the Colonel and his Agent gradually became less and less. The clerical work done by the Agent was taken over piece by piece by the clerks of the Secretary at War; and in a short time Clothing and Purchase were the only two matters directly controlled by the Colonel.

On the principle that the Army should as much as possible pay for itself, profits from clothing were regarded as a legitimate emolument of the Colonels. General Officers got no extra pay as such, i.e., they received pay or half-pay as Lieut-Colonels only. If appointed to be Governor of a Colony, or given some such special command, it was customary for Parliament to vote them an additional allowance. Not always, however, thus Major-General Irving when appointed Governor in the West Indies drew pay only as Lieut-Colonel and owing to the expenses of the position was soon heavily in debt. To such a degree were the profits from clothing regarded as legitimate, that the Finance Committee of the House of Commons, in proposing to abolish the system, considered that compensation should be paid to the Colonels. Its plan was that a Board of General Officers should control the clothing of all the Forces; but the House would not meet the cost of compensation, and the scheme fell through. A few changes in detail only were made - sergeants got 3/ - allowance in addition to the issue of clothing, and greatcoats were for the first time supplied to all troops. On "watch" coats, the Treasury secured an economy by doing away with lapels, the cost of the coat being reduced by Is. 8d. About this time, Napoleon was threatening to invade England.

During the last decade of the 18th century, new regiments were springing into existence like mushrooms - Regulars, Militia, Volunteers, Fencibles, Invalids and regiments of foreign recruits. Often as soon as a new regiment was raised its personnel was drafted to fill up the ranks of an older unit, and the new formation disappeared almost as soon as born. The trade in commissions and in promotions was in a state of boom. A Guards Officer wrote in 1794 : "In a few weeks they would dance any beardless youth, who would come up to their price, from one newly-raised Corps to another, and, for a greater douceur, by an exchange into an old Regiment, would procure him a permanent situation in the standing Army".

An Irish General propounded an ingenious scheme for making recruiting pay for itself out of the purchase of commissions. To raise a new Regiment of 600 men, for example, the cost at £15 per recruit would be £9,000; but the sale of one Lieut-Colonelcy, one Majority, one Captaincy, one Lieutenancy and one Ensigncy, would be £9,250-showing a profit of £250. Again, to increase a battalion for an addition of 450 recruits, a Lieut.-Colonel and a Major might be added. The existing Major would pay for his Lieut-Colonelcy £600; the senior Captain for his Majority £700; another Captain for the junior Majority £550; the two Captaincies thus vacant would fetch £2800; the Government bounty for recruiting 450 men would be £2,250; giving in all a total of £6,900 against £6.750, the cost of 450 men at £15 a head. This scheme was actually tried on a considerable scale, but was an entire failure, owing to the vicious systems of recruiting in vogue.

The indiscriminate manner in which regiments of all sorts were raised and then disbanded, led to an inflation of the numbers of Officers on half-pay. When men of newly-raised units were drafted to older regiments, their mushroom Officers went on half-pay, and remained there, since at the time there was no provision for retiring them. It is recorded that one infantry Officer, for whom a sufficient number of recruits had been raised to form the Royal Manchester Volunteers, remained on half-pay for eighty years, presumably until his death.

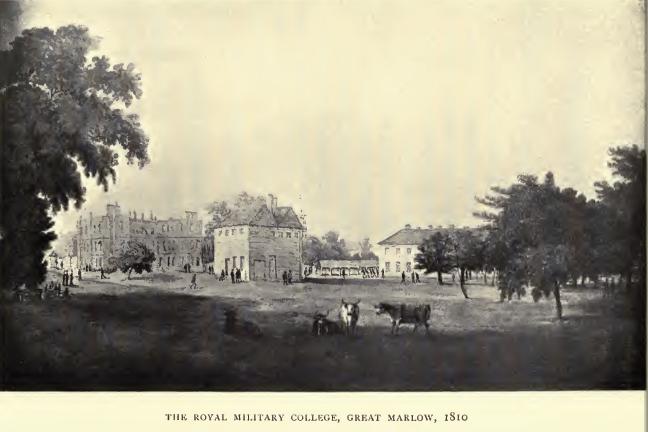

These, however, were mere incidents in a national crisis, during which many lasting innovations were made. The Duke of York the Commander-in-Chief, with the assistance of a Board of Generals, initiated the Royal Military College which began life in 1802 at Great Marlow, and is the present Sandhurst. Provision was from the first, as now, made for the sons of Officers who had died on active service on a free basis, for the sons of serving officers on reduced fees, and for the sons of civilians at higher rates: and after a four years course and an examination, they were commissioned.

The Duke also started a Staff College. The position of the Adjutant-General was strengthened by a provision that only purely financial matters should be handled by the Secretary at War; that questions of discipline and regulations were the exclusive province of the A. G., and quarters and movements that of the Q.M.G. A Military Secretary was appointed; the Duke initiated a system of returns and confidential reports had to be made on all Officers.

Chaplains like other Officers, had hitherto been the personal nominees of the Colonel (who had sometimes dispensed with the Chaplain but not his pay). In 1796 Army, as distinct from regimental, Chaplains were appointed for troops abroad at 10/ - a day and for home troops an allowance of £25 a year was paid to what are now called Officiating Chaplains. A Chaplain-General was appointed; and all the previous regimental Chaplains were put under his authority, or retired on 4/ - a day.

The Surgeons likewise were the colonel's nominees. They purchased. from him their commissions, and were paid by a stoppage from the pay of the regiment. Subsequently they were paid out of Regimental Funds.

In 1747 by Royal Warrant an Apothecary-General was given for himself and his heirs the sole right to supply drugs for the Army. Later, the regimental surgeon received an allowance for medicines in proportion to the strength of the regiment. In 1796. their pay was regulated , medicines and hospitals were provided by Government, fees were abolished, the surgeons were ranked as captains and two years later they had to be in possession of a medical degree, while their "mates" had to pass a medical examination to get a commission.

Veterinary surgeons also were dealt with. Hitherto the farriers had attended to the horses. In 1796 a veterinary surgeon was allocated to every regiment and as sufficient could not be obtained Regiments were given an allowance to cover half the cost of a student at College. They were given a commission with 7/- a day, and a Veterinary Surgeon to the Army was appointed at 10/- a day.

Many other incidents of interest happened during this, the first period of the French Revolutionary Wars. Several regiments got up a voluntary subscription toward the cost of the war, and this was gratefully declined by the Government, when the first Income Tax was levied in 1799. In the same year penny postage was established for letters to the troops serving in Holland. Comforts for the troops abroad were a popular subject of subscription and so many shirts were supplied that the Secretary at War appealed for shoes instead, on the peculiar ground that "the consumption often exceeds the present funds supplying them". The Government also provided for the pay of one Sergeant for every troop of Yeomanry, the Officers and men of which were given pay for two days a week on which they attended drill. I think this is the origin of the present system applying to the Territorial Army.

In a previous note I have described the origin of the practice of housing troops in barracks. Prior to the wars of the French Revolution there were in Great Britain 43 barracks with accommodation for 21000 men. But there were no police in England. The soldiery had to do police work; and for this purpose they could not be distributed in merely 43 centres. They were, accordingly, accommodated in inns, payment being made in accordance with the Mutiny Act, or, as it is now called, the Army Act. With the enormous increase in recruiting in the last decade of the 18

th century, further provision had to be made, and Pitt instituted the office of Barrackmaster-General with powers to construct barracks to house the troops. In this new Department, considerations of economy were the last to be heard of, and both auditors and Treasury were ignored. After a few years it was found that nine million pounds had been spent, and no accounts of any value kept. A large number of Barrack Officers were created, and over 200 barracks were built, with accommodation for 163,000 men.

Yet little was done for the pay of the Army. In 1795 the Oxford militia seized all the wheat and flour they could lay hands on at Seaford in Sussex and sold it at 10/- per sack. Three of the ringleaders were shot; but several allowances were consolidated into an increase of pay together with an increase to meet the increased cost of living. Finally, the mutiny in the Fleet in 1797 brought things to a head. Poundage, and deductions for hospitals and agency were abolished, as well as "arrears," and full pay was ordered to be paid as it became due. The subalterns shared in this reform, together with an increase of 1/- per day.

By the Warrant of 1797, the pay of the Infantry private was raised to 1/- a day, "out of which a sum not exceeding 4/- a week shall be applied to his messing; a sum not exceeding 1s. 6d. a week shall be stopped for necessaries; and the remainder, Is. 6d. a week, shall be paid to the soldier subject to the usual deduction for washing and articles for cleaning his appointments".

It may, at this stage, be of interest to quote the rates of pay of various ranks, as promulgated by the new Warrant. The pay of privates varied from 11¼d. in the Invalids and 1/- in the Regulars to 3s. 2d. in the Life Guards, the latter including Is. 3d. a day for the subsistence of a horse. The Fifer and Drummer got 1s. 1¾d., with a halfpenny more in the Foot Guards. The corporal ranged from ls. 2¼d. in the Line to 3s. 9¼d. in the Life Guards, the latter including the keep of a horse. The sergeant and Paymaster-sergeant got Is. 6¾d.; the Sergeant-major, 2s. 0¾. ; the Quartermaster 5s. 8d.; the surgeon's mate, 4s. 6d. ; the Assistant surgeon, 7s. 6d.; the Surgeon, 9s. 5d.; the Paymaster, 15s., plus an allowance of Is. 6¾d. for his clerk; the Ensign, 4s. 8d.; the Lieutenant, 5s. 8d.; the Adjutant, 8s.; the Captain, 9s. 5d.; the Major, 14s. 1d.; the Lieut.-Colonel, 15s. 11d.; and the Colonel, 22s. 6d. In the Foot Guards, Dragoon Guards, Horse Guards and Life Guards, higher rates were paid, the highest being 47s. per day to the Colonel of the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards. The old allowances for so many fictitious warrant men and hautbois were generally, though not always, included in these figures. The veterinary surgeon in Cavalry regiments got 8s. a day; and there were a number of ranks now forgotten, as, in the Foot Guards, the Solicitor at 3s., the Deputy Marshal at 9d., and the Hautbois at 1s. 6d.

This general, and substantial, increase of pay marks the transition to a professional Army. It took place just before the Peace of Amiens of 1802, which proved to be not a Peace but a breathing-space; and it was left to soldiers serving under the new conditions, up to 1815, to prove that France could not bring Europe to her heel.

End of Part 3

Following a review of military finance, new regulations were introduced between 1797 and 1804 formalising the appointment of Paymasters and the activities of the Paymaster-General

. Lieutenant Nathaniel Hood produced a book in 1804 describing in great detail the regulations and procedures for the Paymaster-General of His Majesty's Forces and for Regimental Paymasters.