RAPC Training Centre Devizes

|

|

Creating the Training Centre

At the outbreak of War in 1939 central training disappeared. Its re-emergence began with the creation of the Officer Cadet Training Unit in 1940. By the end of the War it had been located at Blackheath, Milford-on- Sea in Hampshire, the Isle of Man, High Legh near Knutsford in Cheshire and finally in Marlborough Lines, Aldershot. By that time its output of officers was small; but if Aldershot became its inevitable nadir, its zenith was reached in the Isle of Man. There, not only had technical training achieved high standards, but this had been matched by military training of an intense order. ln 1944, further centralised training on a modest scale was initiated when an Officers' Wing was attached to the OCTU. In addition to general courses dealing with the work of Regimental Pay Offices, there were courses for Field Cashiers and a session of specialised training for Paymasters selected to visit units. Only about half of those attending the latter were selected as Visiting Paymasters, due to the high standard set. While in the Isle of Man there was a visit from King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. This signal honour set the seal of recognition

on the tremendous progress which had been made since the grim beginning at Blackheath in the blitz.

At High Legh the OCTU became, for the first time, involved in systematic soldier training. The creation of the General Service Corps brought this about. Hitherto all Arms had received conscripts direct into their individual organisations. Now basic training was carried out at Army units, this being followed by a period in the Training Unit of the Arm to which the recruit was posted. From the beginning of the War until the advent of the GSC, all categories

of recruits for the Royal Army Pay Corps had gone immediately to functional units, normally Regimental Pay Offices. There, both regimental and technical training had been given using the meagre resources available.

These were hard days for the Commandant of the OCTU, Major Taylor and his diminishing staff. In the face of new commitments they had to move from High Legh to unpromising accommodation at Aldershot in the shape of the disused Connaught Hospital and adjacent buildings. It was now part of the long term plan for the emergent Training Centre that the OCTU and the Depot should be co-located. At this time the Depot remained a separate command under Major Walthew. In order to bolster the permanent staff, Major Taylor requested the early move of the Depot to Marlborough Lines, Aldershot and this was agreed.

A valuable saving in the time of the OCTU technical staff was achieved when the Paymaster-in-Chief agreed that, in future, the technical manual which had been initiated and developed in the OCTU should become the responsibility of the War Office.

Piece by piece the embryo Training Centre was being put together. The components as listed in the revised provisional establishment now included an Administrative Headquarters, an Officer Cadet Training Unit, and Wings for the training of RAPC soldiers; officers and soldiers of other arms; Machine Operators; and for officers of other arms and officers and soldiers of the Royal Army Pay Corps in advanced and cost accounting. The training of personnel from other arms was taken over in 1946 as the Command Pay Duties Schools, were closed. In these schools a high standard of teaching had been achieved and naturally Commands were reluctant to see them go. Efforts to bring about a change in plan were made. Lieutenant Colonel Buck had now taken over responsibility for establishment matters in the War Office (F9) and on behalf of the Paymaster-in-Chief he ensured that the plan for the move of this commitment to the Training Centre went ahead.

The recommendation by the Lightfoot Committee that the Record Office and the Experimental Pay Office should be part of the Training Centre complex was agreed and, in due course, they were phased in.

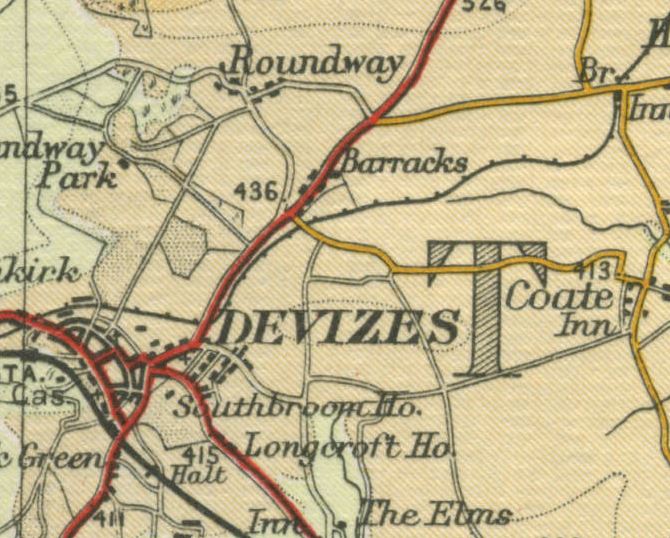

It was soon obvious that the accommodation in the Old Connaught Hospital was not only unsuitable but inadequate. When it became clear that, as a result of the National Service Act and the discontinuance of the General Service Corps, conscripts would have to receive their basic training, both military and technical in the Training Centre, the need for a new location became imperative. This was eventually found at Devizes, where Waller Barracks and adjacent hutted camps had been handed over by the United States Army. The move took place in February 1948. Meantime Major Taylor had handed over to Lieutenant Colonel Blackwell, who took up the duties of first Commandant in January 1947. In December of the same year Major L, G. Hinchliffe joined as Chief Instructor.

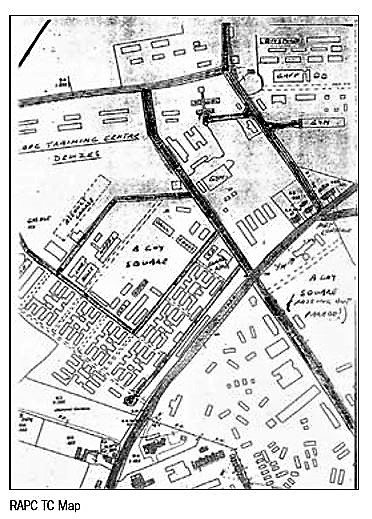

Having done everything in his power to facilitate the move from Aldershot to Devizes Major Taylor went to a well-earned retirement and a new career as a Shropshire flower gardener. The standards were now set for the new era by Colonel Blackwell. He and his successors were to impart a lustre which has never diminished. Meantime, whereas it might have been hard to judge from the original blue print, with its hodge-podge of Wings, what the fundamental character of the Training Centre might be, circumstances, rather than planners, were to decide. The requirement to train conscripts caused it to be designated not only a Corps Training Centre but also an Army Basic Training Unit. As such it took its place with those of all other Arms. Of its three Training Companies two were, in 1948, concerned entirely with the training of recruits, the first four weeks of the syllabus being devoted purely to military skills.

In the history of the Corps no date has more significance than a cold but sunny day in February 1948 when the first intake of National Servicemen arrived direct from civilian life at Waller Barracks, Devizes

The following two articles appeared in the 1965 Corps Journal

Some Reminiscences of the "Good Old Days" at Devizes By an Old Boy of the Training Centre

I arrived in the Training Centre in August, 1949, when it was housed in Waller Barracks at Devizes. I was an Officer Cadet at the time', entering my final 10 weeks, which were to be spent in a combination of Officer and technical training. Among my colleagues were Officer Cadets Bingle and Armstrong, and a number of other National Servicemen who have since left the service. The Cadets lived (very unobtrusively) in the Officers' Mess. None-the-Iess all sorts of loud noises emanated from the rather bleak accommodation at the end of the Mess lines, and indeed there were some very odd characters living there. One Scots cadet warned Officer Cadet Armstrong off using his (the Scot's) shaving mirror, on the grounds that the mercury on the back would wear out at an uneconomical rate if third parties used it. Another chap hated to change his socks; when they were too stiff to get his feet into he would break them and put them in the fire.

Once commissioned, I was posted to 'A' Company in Le Marchant Camp:

Photo: geograph.org.uk - 57733 By Doug Lee

The Company Commander at that time was Major P. A. Stevens, and the Second in Command Capt. Douggie Sterling. The C.S.M. was S.Q.M.S. Hewitt, whose opposite number in 'B' Company was C.S.M. "Buck" Taylor. The Commandant of the Training Centre was Colonel " Nipper" Rees, the Chief Instructor, Major Hinchliffe. O.C. 'B' Company was Major M. J. Davis. The names read now rather like a nominal roll of Chief Paymasters, the more so when the Assistant Commandant of a year or so later is considered, Lieut.-Colonel R. D. Coate.

There were, at this time, some 20 subalterns at the Training Centre. The average age was about 19 and all lived in the Mess, being unattached. We were I fear, rather a trial to the more senior members of the Mess. There was a good deal of high spirited carrying on at night, what with subalterns' courtsmartial, nocturnal raids, and even the occasional explosion when one of Capt. Bill Upington's thunderflashes was dropped down a stove pipe. We had to work hard, however. There was an "intake" of recruits every fortnight, of about 220 men. They were documented, clothed, equipped and squadded in the famous Pipeline as they appeared from the station, and were handed over to the appropriate Company for training. One subaltern might well find himself responsible for a hundred recruits; he would certainly have about 50 on his hands. A comprehensive report had to be written on each soldier after four weeks, so one had to get to know them as soon as possible.

It was the Commandant's invariable practice to tour the barrack rooms in the evening of Intake day. He would speak to the recruits, introduce himself, and see that all appeared to be well. It was Colonel Rees who asked one young man what his hobby was. The youth replied: "I keeps bees". The unwary Commandant, interested, asked what was to happen to the bees, and the recruit replied: "I'm going to flog the buggers". R.S.M. (Harry) Cox was hardly able to contain himself. There were some odd balls among the recruits. One young man appeared in the Pipeline with his mother, who was most anxious to meet the Officer who would be in charge of him. It turned out that I was the one, so I took her aside and was told that he had double vision in each eye, and this I took to mean four of everything. The thing which worried her, however, was that she understood that It was the practice for the Officer to stand in front of the soldiers when they fired on the range. She had, therefore, come all the way from Bootle to warn me to look out for her lad, since I might be in for a surprise. I reassured her (I didn't need much warning !) and in fact the chap concerned turned out to be one of the better shots.

Another recruit, 'A' Company's only regular, gave C.S.M. Offer and me a nasty shock one Sunday morning, when for various reasons the Intake of the time was having an extra drill parade. He broke ranks, rifle and bayonet at the high port, and doubled towards us, apparently intent on mayhem. At the last moment he halted, fumbled in his pocket, and produced what he saId were the plans for the Russian invasion. C.S.M. Offer spoke to him in a clear and uncompromising manner and he rejoined the ranks but after the parade was over he vanished before we could deal with him. I searched the town for him; there were plenty of traces, for he had helped a perfect stranger to spray his car and self; visited a Miss Pitt, residing locally, and scrubbed his anklets in her bathroom, and called in the Elm Tree where he had tipped what appeared to be grass seed in various people's drinks. He .was found eventually by the Town Patrol, and ended in the Netley Hospital. I had a very unpleasant and accusing letter from his father, which upset me more than a little.

One of my prize memories of those days is of the Second in Command of one of the three Companies (not to identify him any closer than that) who was cycling past the Orderly Room with a coal hammer in his right hand. A squad of recruits, under, I think, Sgt. Hardaker, gave him a smart eyes right, and he acknowledged the salute, rather rashly, without letting go of the hammer. He ended, all bicycle wheels and legs, in the chrysanthemums outsideG spider, while the squad disappeared into the distance, nothing unusual having been noticed.

The great thing about the Training Centre in those days, as far as I was concerned, was the Rugby team. We had a great many really useful players, and used to run the show as a club rather than a Unit side. The presence of a number of enthusiasts from South Wales ensured that the game was played hard, and that the singing afterwards was not only prolonged but also harmonious. It is quite an experience to hear a trained choir sing a really disgraceful song. Among the leading lights were Pte. Eddie Dew, now a Sergeant in the Glamorgan Police, Sgt. Harker of the gravel voice, 2/Lieut. Sharpe and a splendid National-Serviceman who played professional Rugby League for Wigan, and who could do the hundred in evens with two men hanging on. We had a good record, but never got further than the quarter-finals of the Army Cup. In 1951 the quarter-finals were at Bodmin, against the R.A.E.C. Our trip there spun out, for various reasons, to five days, and I had a nasty interview with my superiors as a result.

For some reason there was a series of fires in the Training Centre in the course of only a few months. One, I remember, was in, of all places, a water tank above one of 'A' Company's huts. It seemed odd at the time to be spraying water onto a tank containing several hundred gallons of the stuff. Another fire, a bad one, was in the salvage room of G spider. Lieut. Rooney and I were standing on the verandah of 'A' Company office, when we heard the Last Post, as we thought, being played on the bugle. It was a few moments before we realised that the call was in fact the Fire in slow motion, and said so, seeing at the same time smoke coming from the roof of G spider. We didn't know that the Company Commander, Major R. R. Dickinson, was in the "Officers Only" behind us and heard our remarks. He erupted at once, trousers at the carry, and was half-way across the square before he had hauled them into a semblance of decency. Meanwhile the fire was well out of hand, and we had to call the Brigade out as well as the Unit fire party. I can remember sprinting round the block closing windows, only to catch up with a born B.F. who was opening them in the interests of ventilation.

Life in those days was indeed good at the Training Centre. One worked hard , but one also played hard. There was tremendous spirit, and a wealth of enthusiasm. I was, for one, very sorry to leave a place where I spent what are still the happiest days of my service to date.

Some Reminiscences of the "Good Old Days" at Devizes By ANOTHER OLD BOY OF THE TRAINING CENTRE

I read the last issue of the Corps Journal with great interest, particularly the article by "Old Boy of the Training Centre". I'm afraid I recognised him immediately but as there is honour amongst thieves I will not let on.

As may be guessed, I also was there, and the only reason that I felt that I could put pen to paper, was the fact that the author of the article has not yet been Court Martialled, or sued for libel, nor has he yet resigned his Commission. It is quite true, the list of names at the Training Centre in those days reads very much like a nominal roll of Chief Paymasters now, but as well, many of the N.C.O.s are now commissioned and not a few of the then Subalterns are now respected (?) Majors and Captains.

My own meeting with the Training Centre was somewhat different and several months later than "Old Boy's". I arrived in January, 1950, and unlike him I arrived as a "transfer-in" O.R. My very first impression was of the standard of food. I had been used, for many years, to the usual service choice of menu-there were always two choices-take it or leave it! The Training Centre messing was something I had never encountered before, many choices of meats and vegetables, including chops, something I had only associated with Officers' Messes previously. The evil genius, nay the Angel, behind this blessed gastronomic revelation was our Messing Officer. Some time later, after I was commissioned, I remember him "forcing" a Recruit to eat bacon and fried egg. The luckless lad threw his egg away and after much questioning he admitted that he had never had bacon and egg as his "Dad" always had the eggs (this was in the last days of rationing). The Messing Officer made him try one and the young chap ended up by eating four!

Before I reached the dizzy heights of Officer Cadet, I found myself as a L /Cpl. on the "Overseas Training Wing". Here I was the only regular (some five and a half years' service) under two N.S. N.C.O.s. It was at this time that a recruit who had enlisted for 12 years passed through my hands. I being myself, a 12-year man, was exultant here I told my N.S. superiors was a real soldier, a dedicated man who would show them what was what. The first morning on parade there was only one man who had not shaved. The inspecting Officer approached him and asked restrainedly: "You didn't shave this morning, did you?"-"No", answered my champion. "No what?" screamed the Officer. "No razor blade", replied the 12-year man-I never really tried to convert an N.S. man again.

There were others there then, who made their mark, like the Sergeant who told one particular recruit to go home and get out of his sight. He (the recruit) was arrested half an hour later as he attempted to leave the Camp with his kit bag on his shoulder and in tears because he had let us down! We also had one recruit who drank a bottle of bluebell whilst residing in the Guard Room, and yet another who escaped by cutting his way out through the back of his cell using his knife, fork and spoon!

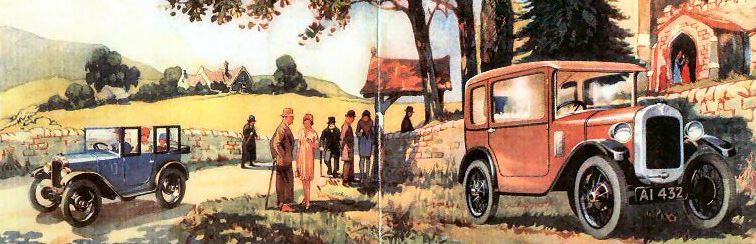

Time went on and eventually I was processed through Mons O.C.S. and the 10-weeks OfficerCadet training at the Training Centre and finally joined "Old Boy" as a member of the Subalterns of the permanent staff. It was then that all the Subalterns had bikes and used to converge on "Strongs Cafe" for coffee on Saturday mornings. There were rumours that they converged every morning but of course that was not true! Bicycles gave way inevitably, to mechanisation and one motor-bike used to drive round the ante-room after dinner nights (assisted by a certain Lieutenant who is now on Costing as a Major), whilst on one night an Austin Seven found itself "installed" after being carried in by exuberant if slightly fortified young (and not so young) Officers. There was also a shortage of coal during one particularly nasty winter and the Q.M. at that time waged a constant war with "Commandos" of Subalterns who were forever raiding his coalyard. At that time, I and another, shared a rather elderly Austin Seven (not the same one that ended up in the Officers' Mess, there were at least three or four on strength) and I remember sitting on top of a sack of coal, while my partner in crime was driving, trying so hard to look innocent, as we assured the Q.M. that we had not seen any suspicious persons in the vicinity of the coal yard. I also remember towing "Old Boys" Austin Seven (circa 1928) back from Bath with mine (circa 1925). On one particularly steep hill I had to get out, use the hand throttle, and push, this was at about six o'clock in the morning and the local policeman's face was worth seeing.

1925 Austin 7 Ad

1925 Austin 7 Ad

Of course it was quite true, we did work, in fact we worked very hard. Working out new ideas for realistic training was always difficult especially when all you could have were three thunderflashes and 10 blanks for 50 men. We used to augment this, out of our own pockets, by buying fireworks and penny bangers. On one memorable occasion, in which I was aided and abetted by " Old Boy", we had bought a slowburning "crow-scarer", a piece of rope with detonators inserted , which you lit and left, every half-hour it went bang. This was too slow for us, we wanted it to go off every five minutes. After much measuring and calculations, we readjusted it and installed it in a pill-box to represent enemy fire. I lit the fuse and went away, 10 minutes later it was still silent so I crawled back into the pill-box to check. As I stood up I realised it was all right, a fact which was forcibly brought home a split second later. I staggered out shell-shocked and dazed to the hysterical laughter of "Old Boy" who was rolling on the ground convulsed. Then there was exercise, "Surprise Packet" in which we supplied troops to make up the strength of a T.A. Regiment and I found myself as a Coy. 2 i/c. This was no small affair, the whole of Southern Command was involved. Sixth Armoured Division and 3rd Lorried Infantry Bde. were versus the rest.

This was indeed a wonderful chance for our recruits (some of them were old soldiers of at least three weeks) and we certainly made the most of it. Our Bn. Cmdr. (T.A.) was a well-known author and military writer and turned up to battle, in fact controlled the battle in our sector, in a vintage Rolls-Royce. "Less likely to be spotted by aerial reconnaissance" , he said. The exercise only lasted three days, but my most vivid memory was of one of our N.S. Corporals and three recruits chasing a tank across a field with fixed bayonets and throwing stones at it. When challenged by an Umpire he said he was carrying an imaginary P.I.A.T. and throwing imaginary "sticky" bombs. I know we were short of weapons (a gas rattle represented a Bren gun) but even I thought this was stretching it, however, the Umpire gave him the verdict and a very irate tank crew were told they had been wiped out by a handful of Pay Clerks.

The only thing we were not very good at on that exercise, was our R.T . procedure and Anglo-Saxon was sometimes substituted for more conventional words; which was accepted, until some electronic freak produced us loud and clear on the B.B.C. Light Programme in Marlborough. If my memory serves me right " Old Boy" was skiving in hospital with something trivial like a broken leg at that time. He talks about the fire in the salvage room in G Spider. I wonder if he remembers the little man who came running in with a bucket of water, and threw it up at the rafters which were on fire, the water came straight back on all three of us and the fire burnt on.

Then there was the recruit who used to fish in the static water tank . . . and the one who brought his chair on Parade because he was tired . . . and then, of course, who could forget the one who stole some false teeth from the swimming pool, and then filled with remorse tried to drown himself standing in 4 ft. of water in the canal? Or the two Welsh doctors who on "pipeline" day, used to stand on either side of a doorway putting a needle in both arms of each recruit simultaneously, talking away glibly in their native tongue, only breaking into English to say "48-49-50 change needles, Dai".

Yes, they were indeed good days, I shall never forget or regret them.