Behind the Scenes with the Pen and Ink Corps! Dr John Black

The role of the Army Pay Services during the Great War in maintaining the loyalty of the fighting soldier and preserving the social fabric of the United Kingdom

John Black

Independent Scholar, Bristol, UK

This paper explores the role of the Army Pay Services during the Great War. On the face of it this may not appear to be a major issue in the overall conduct of the War. However, the Army Pay Services, together with the expansion in depth and scope of separation and dependent’s allowances, and the employment of women resulted in a massive bureaucracy being effectively administered and managed. It is argued that the results of this maintained the loyalty of the fighting British Army and maintained the morale and social fabric of the nation.

August 1914: from peace to war

The argument put forward in this article is an attempt to resolve one of two as yet unsolved questions related to the Great War posed, by Professors Jay Winter and Prost, as follows:

The question driving forward much research in Britain is how to square two facts.

The first is that Britain was in 1914 arguably the most class-conscious nation in Europe if not the world.

The second is the record of loyal service by 6 million men in British forces through four years of war. Where did the militancy of the British working man go?

This article mainly focuses on the second question, although the two questions are interlinked.Previous research on the loyalty of the British Army during the Great War has tended to focus on the regimental system as a plausible explanation for the continued loyalty of the British Army during the course of the First World War. This is despite the militancy of the British working man before the onset of war. The welfare state arrived during the first six months of the Great War in the form of separation and family allowances paid to sailors and soldiers of the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines and the Army. For example, from 5 August 1914 separation allowance was extended to families of all soldiers who were married and already serving on 14 August 1914, and also for those who enlisted after 13 August 1914. These changes were notified in Army Order 319 of 1914,3 and this is further explored shortly.

The British working man prior to 1914 was perhaps not militant in the way that he was politically radicalised or indoctrinated into syndicalist ideals, but was more concerned with his own economic needs and those of his family. This argument tends to be supported through the writings of S. Reynolds, and B. & T. Woolley who in 1911 clarified this argument:

Capital and labour were vague terms, much used in trade union speeches, but not brought home to each man as things make a difference to his Sunday dinner. The working man’s view of finance went very little further than the coin that could be handled and changed, and his main idea was, that money must be circulated somehow … The rich were supposed to have done their whole duty if they spent their money freely, no matter how they acquired it, no matter what sources of profit to the community they keep locked up for their own sport and pleasure.

The deployment of the military to assist the civil powers during the ‘Great Unrest’ from 1911 to 1914 resulted in several civilians being killed in clashes with the military and striking workers particularly in South Wales and Liverpool. Yet this did not deter thousands of men from these areas voluntarily enlisting into Kitchener’s New Army in the late summer of 1914. There appeared to be very little in the way of syndicalist idealism behind the ‘Great Unrest’, other than in terms of economics and financial rewards to be gained through industrial action, and this was well understood by Asquith and most members of his cabinet.

The example of this can be seen in Asquith’s decision to unilaterally announce to the House of Commons that the traditional regimental marriage establishment was to be abolished forthwith and for the duration of hostilities. Therefore a recruit on enlistment, if separated through duty from his wife, was entitled to claim separation allowances. Asquith’s decision was possibly made in the knowledge that most of the recruits volunteering to serve the Colours in the New Army had recently been engaged in industrial agitation and protests where the main argument was about wages. Separation and family allowance entitlement was only for non-commissioned ranks, commissioned officers were not entitled to this privilege. In order to understand the significance of the expansion of separation and family allowances for the duration of the war, some understanding is needed of the very restrictive system of the Regimental Married Establishment thatexisted in the pre-1914 Army.

The official history of separation allowances stated that the issue developed from the existence of the ‘Married Establishment’ that was officially recognised in the Royal Warrant of 1848, although it had existed in a less definite form previously. Trustram’s thesis has provided a detailed account of the workings of the restrictive systems of the regimental married establishment from the mid nineteenth century to 1914, and the official but abysmal treatment of soldiers’ wives who had married ‘off the strength’. In 1871 General Ayde considered marriage an inconvenience to the flexibility and efficiency of the Army. Trustram’s thesis also describes the consequences of soldiers marrying without their commanding officer’s position and ‘off the strength’ before August 1914, and the problems this caused to both civil and military authorities when soldiers’ wives were left behind when regiments embarked for overseas service. Gould commented: Women were regarded as expensive and distracting instead of useful, even essential, suppliers of both services and goods. In the mid-19th century a parliamentary committee judged British Army wives as a ‘great evil and difficulty’; the Naval and Military Gazette described them as ‘a serious impediment to the public service’.

Asquith’s decision terminated an ongoing War Office inquiry into ‘off the married strength’ chaired by Mrs Tennant, the wife of the Secretary of State for War. Prior to the onset of war separation allowance claims for legally married soldiers whose spouses were on the regimental married establishment for the whole of the Regular British Army, was no more than 1100 claims, the soldier being entitled, if duty took him away from the family home, to quarters in the garrison where he was serving. With the immediate changes, by November 1914 separation allowance claims had reached over half a million. Previously under official regulation regarding separation allowance in force prior to 5 August 1914, separation allowance was issuable to families of:

(a) soldiers on the Married Establishment (which constituted the majority ofthe 1100 claims annually),

(b) reservists permitted to rejoin the Colours,

(c) reservists and special reservists called out on permanent service,

(d) special reservists during annual training (Army Order 193 of 1914),

(e) Soldiers of the Territorial Force when embodied and, under certain conditions during annual training.

Also prior to August 1914, separation allowance had been issued to a legally married spouse of a soldier on a monthly basis. However, from 12 October 1914 the issue of an ever increasing entitlement to separation allowance was made on a weekly basis and the payments were to be made at post offices through a new postal draft in the form of a cheque book containing thirteen sheets. Army Order 440 of 1914, promulgated on 1 January 1915, made provision for ‘Separation Allowance for dependants of soldiers other than wives and legitimate children during the present war’. Such dependants represented a ‘member of a family’ that included:

(a) The soldier’s father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, stepfather, stepmother, grandsons, granddaughter, brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, (‘grandson’ and ‘granddaughter’ will include illegitimate children of whom the soldier is the grandfather and the illegitimacy of the soldier himself will not affect the position of his parents or grandparents).

(b) A woman who has been entirely dependent on a soldier for her maintenance and who would otherwise be destitute; and children of the soldier in charge of such person.

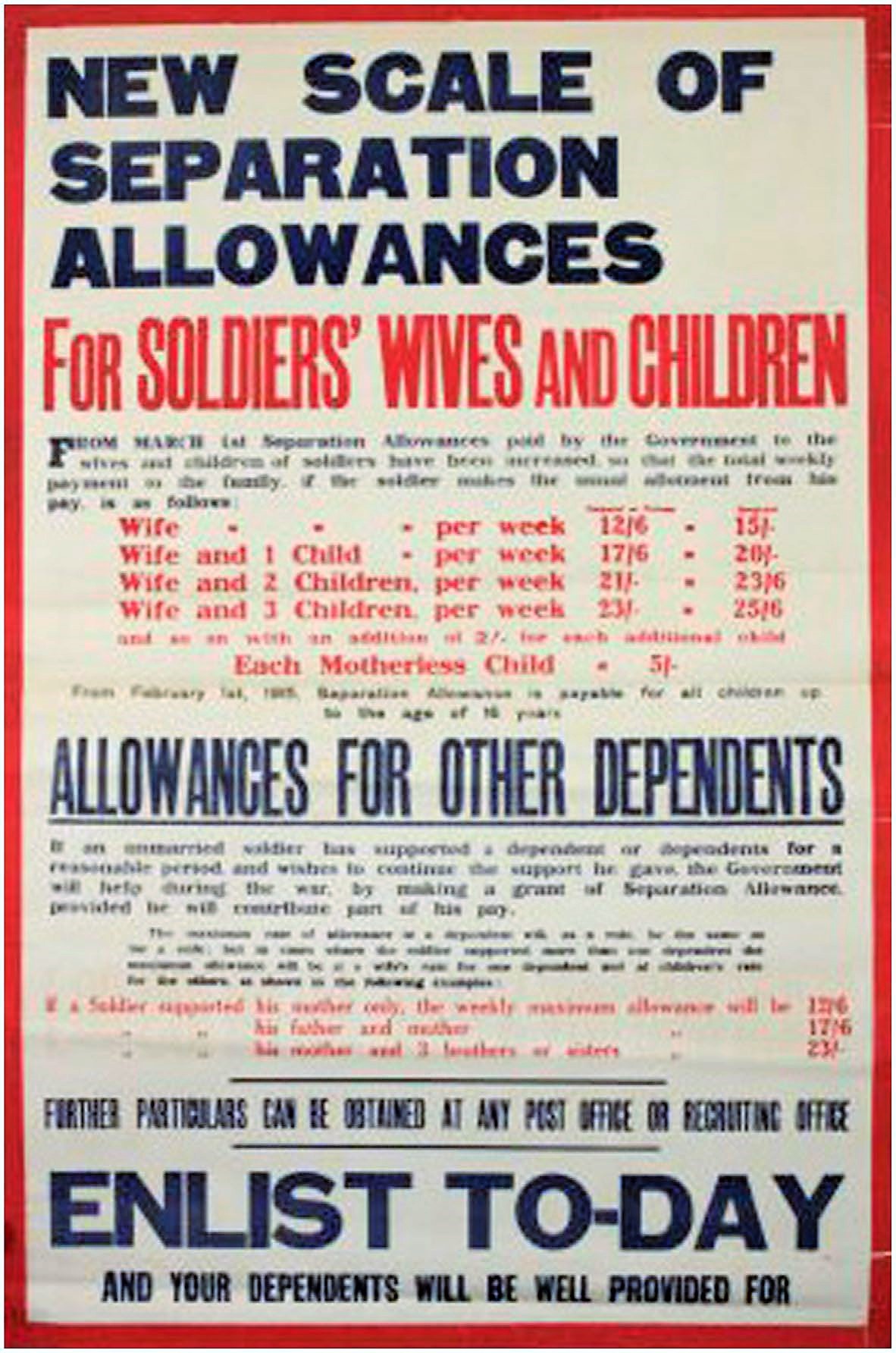

Women in a common law relationship with a soldier became entitled to separation allowance and were identified in official documents as unofficial wives. Pedersen’s thesis argues that the suspension of ‘marriage off the establishment’ and the introduction of separation and family allowances on a broader basis represented the state as a surrogate husband. Practically it was more likely ensuring the loyalty, or to be more precise, of buying loyalty for the masses now flocking to the Colours. The details of these changes were publicised on posters that were displayed in prominent public places including post offices, railway stations and places of entertainment in early March 1915. The poster gave details of rates of allowances and who were entitled to them, and the poster was aimed at voluntary recruitment (Figure 1).

Until January 1918, separation allowance was dependent on the soldier making an allotment from his pay. Also an allowance of three shillings a week was paid to soldiers who were billeted in their own home and, if married, the soldier’s wife or partner andchildren, both legitimate and illegitimate, were also entitled to family and children’s allowance. Entitlement to separation allowances could be withdrawn through misconduct of the recipient. The War Cabinet estimated that the first year of the operation of the new scales for both the Navy and Army would be £50, 500, 000; and for the second year £54,000,000.

FIGURE 1 Poster issued in March 1915 advertising new rates of separation allowances. These posters would have been displayed in public places, i.e. post offices, railway stations public libraries. By kind permission of the Imperial War Museum.

The major military establishment which administered the soldiers’ pay and allowances was the regimental pay office, and in 1914 there were twenty-seven of these fixed centred pay offices that administered the soldiers’ account records in Britain and Ireland. Most were small, having no more than twenty to thirty all-male military and civilian staff. The largest was the Regimental Pay Office Woolwich, which had a total staff of ninety before August 1914. An observation of the Regimental Pay Office Lichfield in 1914 by a junior regimental officer of the Royal Artillery who had responsibility for the accounts and cash of his regiment, noted the smallness of the office and commented that I didn’t belong to the [Royal Army Pay] Corps, I had to go about the accounts of my Unit. I rememberthinking how small that office was, and the work was all done in pen and ink. But perhaps because of the simplicity of the pay code then, a small office could look after a lot of Units and the clerks surprised me by their personal knowledge of the men and their families in their Units.

It was the responsibility of the regimental pay office to submit to a soldier’s unit a monthly pay list. This was used by the regimental commander to pay the soldier his due entitlement on a weekly basis. The pay list was then returned to the relevant regimental pay office in order that his account was updated and balanced. Increases in soldier’s pay, the payment of National Insurance, and hospital charges were administered by the regimental pay office. The soldier’s United Kingdom-based record office administered a soldier’s record of service, including taking on strength, postings and transfers, promotions and demotions, trade or skill classifications for purposes of pay, the award of honours; mentions in despatches, commendations and medals; and the reporting of a casualty notice in the case of death, serious injury or illness, and hospital admission and discharge. The record office notified the regimental pay office of issues relating to court orders and paternity orders that amounted to compulsory stoppages from pay. In many cases, the record office and regimental pay office were located on the same campus, normally with the depot establishment of the infantry. For example, Winchester was the Depot (Peninsular Barracks) of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps and the Rifle Brigade; similarly in 1914, the Army Service Corps both the regimental pay office and record office were located at Woolwich Dockyard. The commanding officer of a regimental pay office was normally a senior officer of the APD at the rank of colonel, and known as the regimental paymaster. Before August 1914 it was common practice to employ ex-military personnel as civilian clerks, known as writers, which was a common grade within the contemporary home civil service. In some cases boy writers were employed who were young men aged under twenty-one and in a number of cases some were the sons of serving APC senior non-commissioned officers. However the structure of the administration of pay was not so clear-cut. For example, during the First World War separation allowance payments to the wives and other dependants of soldiers of the Territorial Force were administered by county Territorial Force Associations. The reason for this arrangement is not known, but it added to the complexities of the bureaucracy, a point discussed later.

Although the changes to the separation allowance system appeared to be altruistic, the expanding system also led to a bureaucratic war that was not anticipated either by Asquith, nor the Secretary of State for War. With the expansion of the Army many being recruited were now entitled to a wider range of separation allowances. But the Army Pay Services had not expanded, and generally still remained a very small cog in an ever increasing bureaucratic and politically sensitive machine. Specially enlisted clerks were recruited into the APC, as military clerks, along with civilian male clerks. Few volunteers were found as most male civilains clamoured to join the New Army battalions.

The Army Pay Office Woolwich, which in August 1914 was the largest with a total male staff both military and civilian of ninety, was responsible for the accounts of the largest logistics corps in the British Army, the Army Service Corps, and the two largest regiments, the Royal Field Artillery, (RFA), and the Royal Horse Artillery, (RHA). By mid-August 1914 the Woolwich pay office was deluged by a paper war and the regimental paymaster (the commanding officer) accepted the voluntary and unofficial assistance of the ladies from the garrison.

The expansion of allowances and pay, and the beginnings of the bureaucratic war

By late October 1914, when the pattern and frequency of payments changed from monthly to weekly, and the influx of recalled reservists and the enlistment of soldiers and the thousands of separation and family allowance claims had increased the paperwork to insurmountable proportions, the War Office Finance Branch ordered the women out. But in late October 1914, it was the War Office Finance Branch that found itself under pressure with a shortage of staff. The War Office therefore began to officially recruit women staff, firstly on loan from the General Post Office (GPO) and Post Office Savings Bank, (POSB), and in November 1914 through openly recruiting women clerks as temporary civil servants; the loaned Post Office women became supervisors to the ever increasing recruitment of civilian women clerks.

The policy of employing women expanded to include the UK-based army and command pay offices from January 1915, and lady superintendents to be responsible for technical management and welfare of women staff, began to be recruited from January 1916. By the end of the war, the UK-based Army Pay Services departments employed thousands of women. One senior paymaster, writing in 1920, commented on the arrival of women clerks into APD establishments, ‘with [their] flower vase, powder puff and tea-pot’.

Debates in the House of Common for 11 November 1914 included issues such as the administration of separation allowances. Harold Baker, the Financial Secretary to the War Office, acknowledged Asquith’s ‘most wise and generous’ unilateral decision to suspend ‘off the strength’ marriage, but also acknowledged the administrative problem that it had caused.

Until 18 August 1914 the War Office Finance Branch consisted of two departments, Accounts 1 and 2. Two functions, amongst others, of Accounts 2 were the responsibility for executive decisions on separation allowance claims that had been referred there by regimental paymasters, and the administration of disposal of effects of deceased soldiers. The executive staff of Accounts 2 responsible for appeals on separation allowance claims numbered two, and for administering the effects of deceased soldiers there were three. By 1919, the Finance Branch at the War Office had increased to 6 departments. Accounts 3 was responsible for separation allowances, multiple claims and from 1915 appeals.

“In peacetime 1,100 women received separation allowances. At this moment there are half a million … Suddenly there was thrown upon the resources of the War Office … To avoid any delay at all, and in order to deal efficiently with these numbers, we told the paymasters that they were to act on prima facie evidence and pay at once and we would verify afterwards.” (

12 November 1914, In the statement by the Financial Secretary to the War Office)

Recruiting offices were also swamped by the added workload of having to attest hundreds of men. The Recruiting Committee, authorised to recruit the Universities and Public Schools Brigade of the Royal Fusiliers in London, was overwhelmed by a sea of bureaucracy where:

Five thousand attestation forms had to be duplicated, and a likely quantity of pay sheets and medical history forms to be filled in detail, and the knowledge that the welfare of 5000 men depended on their accurate completion.

The Financial Secretary to the War Office noted the amount of incomplete correspondence arriving at the regimental pay offices, including where the address of the payee was not given, or the omission of the soldier’s name, regiment or other particulars. Marriage and birth certificates arrived without covering letters, and in many cases problems arose where soldiers had the same names, a problem particularly noted with Welsh regiments.

In addition, in some cases married soldiers were enlisting and failing to declare their marriage or their children, as they may have abandoned the family, this particular problem was more apparent with the recall to the colours of regular reservists. Baker noted that new staff had been recruited but these had to be trained and it was a long learning curve. Great efforts were made to administer the new separation and family allowances as efficiently as possible, particularly in sensitive areas noted for previous unrest.

From its depleted and stretched resources the War Office established mobile army pay offices that were deployed to sensitive areas in order to administer separation allowance payments. The only apparent evidence of their existence comes from contemporary parliamentary papers. In addressing the House on 12 November 1914, Harold Baker announced:

“We have learned from Honourable Members the state of affairs, special officials were immediately sent out from the War Office to temporary pay offices to deal with the matter, and to take whatever measures they thought necessary immediately without reference to us in order to meet the local difficulty. I see the Right Honourable Member for West Birmingham [Sir Austin Chamberlain], in his place and I am sure he will corroborate with me when I say that an appeal was made by him, and we did meet, and the same applies with regard to appeals made by honourable members from Wales. These honourable members will corroborate with me with regard to the serious difficulties that arose in South Wales, partly owing to the number of people of the same name and partly owning to other difficulties. We set up special staffs in temporary offices, and they have been working night and day to deal with the applicants on the spot.”

He continued by stating that advertisements had been placed in the press and other locations inviting those with grievances to visit the War Office where their complaint would be dealt with on the spot. The Financial Secretary assured the House that in his view the number of arrears were now very slight, but he did invite honourable Members who had knowledge of grievances from their constituencies, ‘and if they follow the directions given, and if on writing to the Paymaster a woman fails to establish her claim, then they should refer the matter to the War Office’.

An exploration of Hansard from August to November 1914 reveals very few complaints regarding the separation allowance administration. These included one general question and two complaints related to individual soldiers, all raised by the same MP. The first concerned a soldier in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps who had enlisted at Winchester on 28 August 1914. It was alleged that the Regimental Paymaster had failed to answer four letters of inquiry from the local Soldiers and Sailors Families Association (SSFA), all sent in October 1914. The Regimental Paymaster only responded when the local SSFA office sent a telegram. A second matter related to a soldier of the Royal West Kent Regiment whose compulsory allotment to his wife at 4d a day was well below the minimum required at 8d a day. Apparently the Regimental Paymaster Hounslow was deducting 4d a day (2s.4d a week) from her weekly separation allowance of 21 shillings, her weekly remit being reduced to 18s.8d a week. It was suggested that the soldier in question should make up the 4d a day and not the wife as part of his weekly compulsory deduction.

The number of issues raised in Parliament regarding the promptness and efficiency of the pay and allowance system was generally minimal. Hinchliffe commented that a Regimental Pay Office would receive between 20,000 and 30,000 letters and vouchers each day. Paper moved by the van load. Further, the initial rapid expansion of the Army had often put square pegs into round holes. As a result, transfers between regiments were counted in hundreds and thousands. Every time an individual soldier was transferred,his papers had to be moved from one fixed centre (regimental pay office) to another.

A major bugbear was when items could not be traced. Papers prepared in recruiting offices and urgently required by Regimental Paymasters found their way, all too frequently to the incorrect regimental pay office. Apparently, according to the ‘Behind the Scenes’ articles, the major priority in August and September 1914 was the administration of separation allowances and advancement of pay to recalled reservists. The process included making out money orders which was very labour-intensive. The delays were mainly caused by reservists giving insufficient details of their next of kin, as previously mentioned. Staff at regimental pay offices received abusive letters or were confronted by equally abusive relatives. The regimental paymasters and their staff just accepted this as part of the task at hand and carried on regardless. Regimental paymasters used their own or collective initiative and made decisions on the evidence they were faced with, despite any regulations to the contrary — which were changing on an almost daily basis.

It appeared to some politicians and military officials that the reforms of separation allowances particularly favoured married men and that there may have been more married men enlisting than unmarried men. L. Chiozza-Money, a Liberal MP and economist, informed the Prime Minister in 1915 that his attention had;

"

Been directed to the fact that ten out of twelve of the men of this country aged thirty-nine to forty are married, and that most of them have children, and if he will, in view of the undesirability of accentuating social difficulties and of creating enormous liabilities for the State, consider the restoration of thirty-eight as the maximum age for recruits? Asquith’s reply included the fact that the extension of the age limit was to widen the field of recruiting, and to give men eligibility to enlist who had previously been barred from enlistment and opportunity to serve their country."

Nevertheless there were a sizeable minority who believed that conscription should have been introduced in 1914, one such example was Lieutenant Colonel James Grimwood. Grimwood was a recalled Regular Reserve officer and in September 1914 was appointed as adjutant of the 7th Battalion, South Wales Borderers, a Kitchener New Army battalion recruited from the Glamorganshire coalfields that had recently experienced serious industrial unrest. Writing in April 1919, Grimwood considered that had the cost of administering and paying separation allowances been known to the Government in the early months of the war, then it would have,

“

Exercised a tremendous pressure upon Cabinet Ministers and would have pointed to the fact that that from certain districts in the United Kingdom it was the father of families that voluntarily enlisted whilst the single men were not coming forward. I was in command of a Welsh battalion and when it was formed in August 1914, I knew that something like 90 per cent of the men were married men with families, whilst the bachelors were remaining at work in the coal mines.”

The reforms of separation allowances for 1914 and 1915 were incorporated into a manual called Regulation for the issue of Separation Allowance and the Allotment of Pay published in August 1915. An amended manual was published in 1916, the title had changed to encompass the change in the scope of separation allowance, called Regulations for the issue of Army Separation Allowance, Allotments of Pay and Family Allowance during the Present War and a third revised manual was also published in December 1918. In all three publications separation and family allowance was defined as issued at the discretion of the Army Council. Its object is to provide for the maintenance of the family of the soldier when he is unavoidably separated from them by the exigencies of public service, or in maintaining the dependents of the soldier, other than wives and children in the same degree of comfort as they enjoyed prior to 1 October 1914 (or to enlistment if later). The issue of separation allowance is ordinarily dependent on the soldier making an allotment of his pay.

The last sentence was omitted from the 1918 publication as the major reform there was that separation allowance was no longer dependent on the soldier making an allotment from his pay. However under Army Order No. 1 of 1918, the rate of a soldier’s daily rate of pay increased by a generous amount and included pay for special skills, such as instructor’s pay. The abolition of the soldier’s allotment as a qualification for separation allowances may have been a reason for the increase in voluntary recruiting in 1918, particularly during the last months of the conflict. The 1918 increases in pay and allowances were granted in two stages. This, according to Pedersen, ‘owed much to both parliamentary pressure and fears of unrest in the Army’.

The publication of three manuals, twice in 1916 and the third in 1918, represent the three phases of reforms related to separation and family allowances. The 1916 edition includes the reforms from August 1914. Indeed, the 1916 edition perhaps relates to the more radical reforms with the recognition and acceptance of multiple claims, which were in respect of ‘an allowance for persons who were dependent on more than one soldier and no one could foresee the enormous work which they ultimately gave rise, and where more than one paymaster was involved’. An example could include a woman whose husband or partner and sons were serving in the Army or Royal Marines, Royal Navy, or where the woman had sons and a partner serving in the Army, the serving sons being the offspring of different biological fathers.

Initially in 1914 where a multiple claim was made that involved two or more regimental paymasters; by agreement one paymaster would issue one postal draft book to the payee. The paymaster issued payments within approved limits and all claims were reviewed by the War Office Finance Branch. In January 1915 the system was reviewed, and claims were now received by the War Office, they could not exceed the maximum admissible.

In February 1915, a special issue section was established at the Command Pay Office, (CPO), London District which received all multiple claims that exceeded the maximum admissible. In March 1916 the newly established Accounts 3 was formed at the Finance Branch of War Office. Accounts 3 became responsible for auditing all multiple claims approved where the amount of the allowance exceeded twelve shillings and six pence. Also a Separation and Family Allowance Tribunal was established as part of Accounts 3 to adjudicate on appeals.

If the claim did not exceed the maximum allowed then it was assessed by the Command Paymaster and if correct was passed for payment. In the case of discrepancy or dispute then the claim was referred to the Separation Allowance Appeals Tribunal. The high water mark was in March 1917 when the total number of wives and dependants rose to 3,158,000.

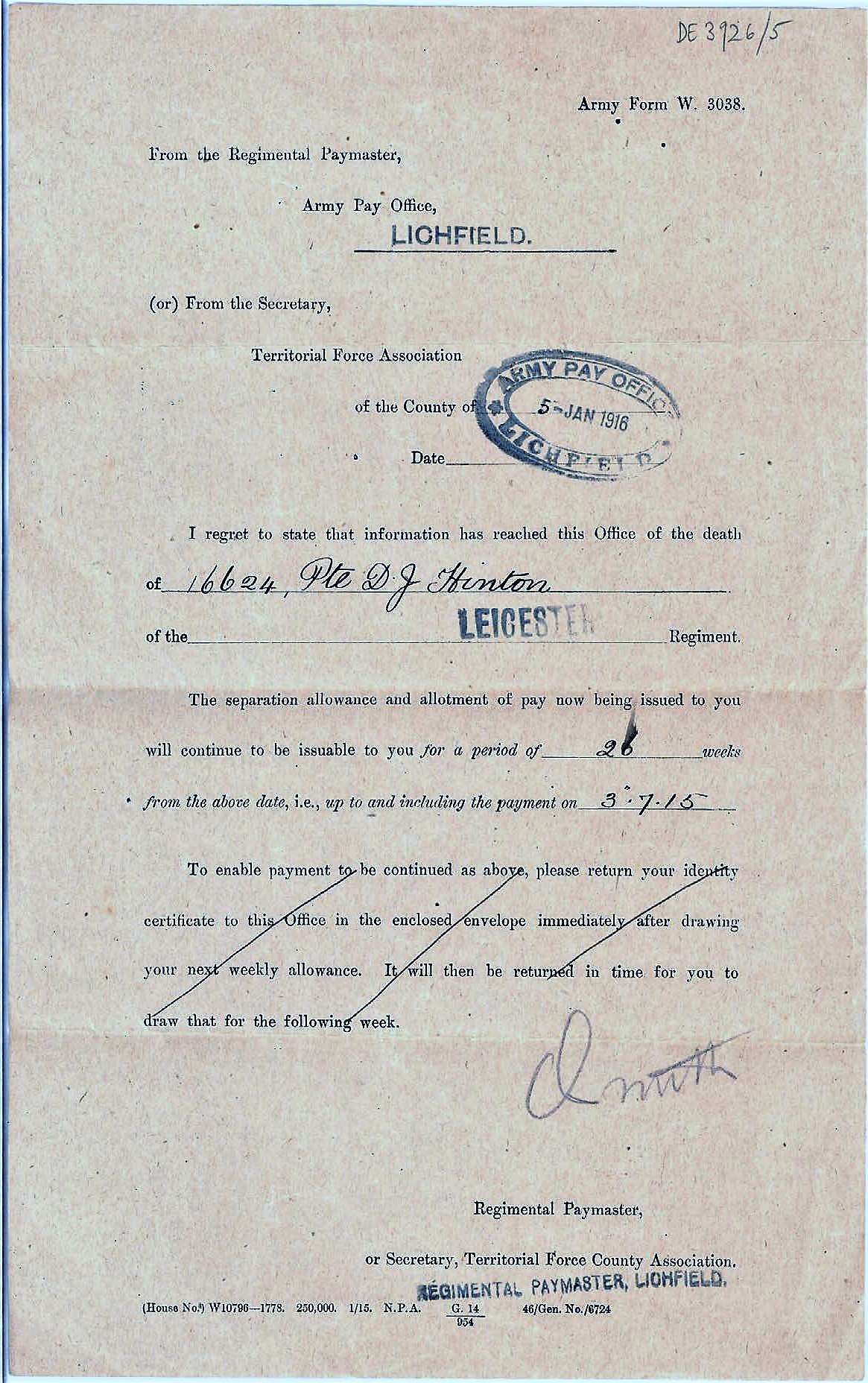

One major reform of the revised separation allowance entitlement was where a soldier was killed in action, when his wife or other dependant could continue to draw separation allowance for twenty-six weeks after the soldier’s death. Notification to the wife or dependant to this entitlement was made by the respective regimental pay offices or, in the case of a soldier of the Territorial Force, through his local Territorial Association. An example of this is given below, which was issued by the Regimental Paymaster, Lichfield on 5 January 1916 to the widow of 16624 Private D J Hinton, 1

st Battalion, the Leicestershire Regiment, who was killed in action (gassed) on 20 December 1915 in Belgium.

Evidence of an ‘error friendly’ system?

In assessing whether the temporary system of separation allowance reforms during the Great War was the major catalyst that prevented any mass mutiny in the British Army, it is pertinent to point out that the system generated by the wartime pay and allowances reforms was very bureaucratic and what can only be described as ‘error-friendly’.

One major reason for this was due to the regimental numbering system of soldiers that changed every time soldiers were transferred, the majority being compulsory transfers. A transfer could mean that the soldier’s record office and regimental pay office changed, and it was common for numerous compulsory transfers of soldiers during their period of service during the Great War.

During the course of the First World War, the APC had to face accusations that they were ‘shirkers’ housed in ‘safe billets’. This is despite the fact that many soldiers who were medically downgraded through injury or sickness were compulsorily transferred into a clerical role with the APC. Indeed the APC by 1916 was considered a reserve that fed the front line. A mobile medical board was established that visited every command or regimental pay office every six months. Soldiers who were upgraded to C1 were then transferred to a front line regiment. This scheme provoked rumour and speculation. For example, a question was raised in Parliament in 1918 where it was rumoured that 200 APC soldiers at RPO York who were medically reassessed by a travelling medical board that consisted of a single doctor who passed thirty per cent fit A or B1 for operational service, whereas three months previously the same men had been assessed and found to be medically unfit for active or operational service at C3. The suggestion was that there had been a lowering of medical standards in the Army, or that the impossible had happened as 200 soldiers had recovered in a short space of time.

A similar case related to the Regimental Pay Office No 2 Blackheath, where it was rumoured that 120 soldiers of the APC were to be compulsorily transferred to the Labour Corps. Most had been clerks or schoolteachers prior to 1914, and a large number had found themselves in the APC due to being medically downgraded from front-line units either due to previous operational duties or had been found to be medically unfit on enlistment and directed to duties with the APC. The tasks of the Labour Corps required exceptionally fit men, not those who had by their age and sedentary lifestyle been deemed medically unfit for the onerous heavy duties required by the Labour Corps.

The Financial Secretary to the War Office supported the work of the APC against accusations of shirking and in numerous cases suggested that to move en masse APC soldiers regularly every six months would do little to enhance the total efficiency of the Army Pay Services.

Part of the duties of the regimental pay offices and the local Territorial Force Associations was to prepare identity documents for wives and dependants entitled to separation allowance, as previously noted. Perhaps the most scathing criticism made by the Report of the Committee on the Pay Office Organization in 1919, that was chaired by John G. Griffiths, a Treasury official. This highly critical Report was scathing over the duplicate but unnecessary system between the Regimental Pay Office and Territorial Force Associations. Another complaint, made in 1918, related to the method of communication and suggested that regimental paymasters were inconsiderate in the lack of simplicity and legibility of their communication to wives and dependants, as well as in regard to unnecessary repetitions of requests for information.

The example in question related to the case of the Regimental Paymaster Army Pay Office Woking, regarding the wife of a soldier of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) who had been injured in action in France. The wife was requested to send her marriage certificate and birth certificates of their children in order to verify her allowance, which she had done previously on three occasions. However the crux of the complaint raised by her MP was the method of communication through the means of pencilled letters, instead of letters plainly written in ink or typewritten.

In his reply, the Financial Secretary stated that he would make inquiries regarding the case, but commented that it was quite impossible to provide typists and machines to cope with all the correspondence in regimental pay offices. Pencil was used instead of ink as it allowed the necessary copies to be made for retention in the RPOs. But this was not enough for the enquiring Member who queried whether a pencil was used in communicating with officers and their relatives? The use of typewriters would have delayed the preparation of replies and communications with other government department, and relatives of soldiers, and commanding officers of regiments and other military units.

Overriding the bureaucratic complexities through gender integration and the use of old and new technology

From January 1915 the War Office sanctioned the employment of women as temporary civil service clerks within all UK-based Army Pay Services establishments, supplemented with the recruitment of lady superintendents one year later in 1916. The women became an integral part of the Army Pay office organisation, and integrated successfully into what had been an all-male military environment. The women staff of the army pay offices gave these establishments a sense of permanence, counter balancing the otherwise transient population of APC soldiers as previously mentioned.

Also the inclusion of new technology together with the efficient use of older technologies made for the smooth running and efficiency of what could have been an error-prone system. These two factors are incorporated into the following four examples that made for an efficient system of running and organising a very bureaucratic system:

First, there appeared to be little in the way of mass public complaint over the administration of pay and allowances to soldiers and dependants during the Great War. This suggests the efficiency of the Army Pay Services and the administration of pay and family dependant allowances. An exploration of the Times Newspaper Index from 1914 to 1920 only revealed two letters related to the Army Pay Services, and only one of these reflected a complaint. The first letter was written by L. C. Evans, Town Clerk of Salford, who ommented on the outdated methods used by the Army Pay Offices, and suggested that SSFA locally could run the system more effectively:

“

As honorary secretary of the Salford Branch of the Soldiers and Sailors Families Association since August 1914 I have had to deal with every regimental paymaster in the United Kingdom, and I make bold to say that a clumsier more out-of-date system than that of the Army Pay Office could scarcely be devised. Many thousands of Salford men have joined the Army, and their dependents are, nearly in every case, still living in the borough, and we could pay every one of them and keep the accounts under proper instructions of the War Office without difficulty.”

The Times published a response to this complaint some days later, the signatory calling herself ‘Fairplay’:

“

Suffice it to say that in my opinion there is little wrong with the system, but I can say that the complexities to be dealt with would, to my mind, cripple any system unless a staff of nothing but experts could be devoted to it. As regards the staffing of the offices, the number of men employed has been reduced to a minimum, the bulk of the purely clerical work being carried out by lady clerks. Comptometers and other labour saving devices have been introduced, and every effort is made to run offices on business like principles. The numerous business and professional men brought in as acting paymasters have in but extremely few cases been able to suggest any improvements on the schemes devised by the regular departmental officers for carrying out the work effectively.”

(‘Fairplay’, the signatory to the letter, was in fact a lady superintendent at RPO Woolwich. Ruth Jane Fairplay had been born on to the regimental married strength, her father being a colour sergeant in the Loyal (North Lancashire) Regiment. She was mentioned in despatches in September 1918 for her work at RPO Woolwich)

The second was the abolition of the restrictive regimental married establishment that existed prior to August 1914. Its abolition was made unilaterally by Asquith, the Prime Minister, who was perhaps astute enough to realise the potential of the politicisation of the British Army in the wake of the Curragh Incident immediately prior to August 1914, and the real threat of civil war in Ireland. Asquith was also very aware of the potential militancy of the British working man, as had been manifest in the years of the ‘Great Unrest’ preceding the First World War.

The third was the extraordinary change in the regulations within the separation allowance system that included the introduction of family allowances, including a form of child allowances, and allowances paid to the families of unmarried soldiers. These allowances were made on a blind-need basis, and until January 1918 were issuable so long as the soldier made an allotment from his normal pay to the payee. The acceptance of conditions in the social fabric of British society that included the recognition for multiple claims from 1916 was perhaps the pinnacle of this acceptance, and pacified the incoming conscript army, as family allowances had pacified the Kitchener New Armies in 1914–15.

Fourth was the acceptance of new technologies, including the adoption of loose-leaf binders, as well as the efficiency of older technologies, together with the professionalism and sheer determination of the military and civilian staff of the Army Pay Services during the Great War. Until 1914 the accounts of soldiers were kept in leather-bound ledgers that were immovable and fixed. The regimental pay offices were small with a handful of staff, and separation allowance claims were few due to the official regimental marriage establishment. The offices themselves perhaps were more in keeping with a Dickensian office.

Also developed was the ‘slip system’ that made the identification and distribution of pay lists, vouchers and other documents easier to identify and disseminate. The system was simple to use and perhaps deskilled parts of the clerical procedure that made it easier to train up new staff recruited on a temporary basis into the regimental and army pay office, a point emphasised by ‘Behind the Scenes’, which commented:

“

In this respect the Slip System was a godsend; for it enabled pay offices to use considerable numbers of untrained staff … This system was introduced into Shrewsbury early in the war by Colonel Campbell Todd, and afterwards extended to all offices. It proved a great success and helped regimental paymasters in no small way to pull through. Most of them were convinced that they couldn’t have carried on without it.”

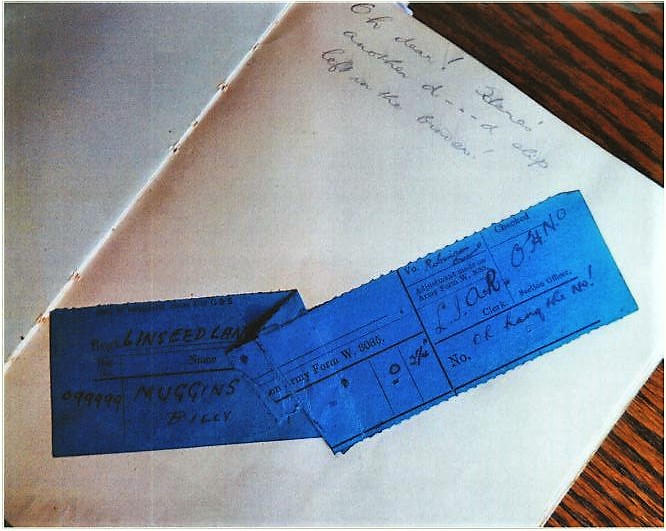

The ‘Slip’ colouring system was used for convenience of identification and sorting; for example blue was for acquittance roll, green for pay and mess book charges, and yellow for casualties. The 1919 Griffiths Report commented on the Slip System as follows:

“

To meet the difficulty … the following system had been devised: - The Central Section of the office extracts from the documents the particulars of the transaction to be entered on the individual ledger sheet and records them on a ‘slip’ form which it sends to the ledger section, retaining the original document until the ‘slip’ comes back with evidence of posting when it is attached to the document … To secure their return to the central section they are serially numbered before despatch to the ledger sections, corresponding numbers being recorded on the original document.55

Griffiths also commented that although the Slip System afforded an effective control, it was very labour-intensive, and the Committee, following their investigations, were staggered to find about 250 clerks, i.e. about one-eighth of the whole staff, engaged in ‘making out, sorting out, despatching, receiving back, re-sorting and fastening together hundreds of thousands of slips’. According to the Committee, the system could introduce a new source of error.56 The fact that the Slip System worked, reflects the efficiency of the staff employed working the system, (many of whom were women clerks), of many small cogs within a large bureaucratic machine.”

In January 1915 Colonel A. B. Church, Regimental Paymaster Woolwich, went to the War Office and ‘begged to be allowed to use a loose-leaf binder account for each soldier’, an example of which he brought with him, and pointed out that he could not carry on without it. Colonel Campbell Todd, Regimental Paymaster, Shrewsbury, was also to the fore with the loose-leaf binder, and had introduced them into the Regimental Pay Office Shrewsbury. The two senior APD officers were responsible for the ultimate introduction into all army pay offices of the loose-leaf binder (RAPC Journal, autumn 1935, 133). In the May 1916 edition of the Army Pay Corps Gazette is an advertisement for a Kalamazoo loose-leaf binder. See Hinchliffe, Trust and be Trusted, 80–1 for the post 1918 development of the loose-leaf binder in terms of regimental pay office use.

An example of a blue slip that was extensively used in the internal management of Army Pay Office organisation, and identified the location within the respective pay office of a soldiers pay record. The writing on the page of the autograph book says, ‘Oh dear! There’s another d–d slip left in the binder!

The introduction of the Slip System, which was labour-intensive and probably deskilled the clerical function of APC personnel, particularly women clerks, was in essence the oxygen supply, as it were, that kept the regimental pay offices running efficiently, despite its labour cost consumption. At that time the luxury of punch card systems had not been developed and the Army Pay Services had to wait for a second global war before such technology was available.

The slip system was not designed primarily to be ‘girls work’, yet many women clerks were employed on operating the Slip System. Colonel Blakemore, Regimental Paymaster Hounslow writing in 1920 clarifies this point when he praised the rank and files staff of the regimental pay offices including, ‘the enlisted and civilian, male and female, types of nearly every section of the community, the machine that did the work, our comrades through five long years,

An example of a blue slip still exists, as one is preserved in Miss Amy Taylor’s autograph book that she kept whilst employed as a temporary civilian clerk at the Regimental Pay Office, Woolwich from 1916 to 1920. Apart from the introduction of Kalamazoo loose-leaf binders, other developments included duplicators and comptometers. These existed alongside the labour-intensive slip system, and the traditional pencil and memorandum system of communicating with soldiers and their dependants.

Value for money?

There is little doubt that the administration of pay and allowances to the fighting British Army was expensive, but so too was fighting a global war. In both world wars, expense was secondary to financing the fighting for final victory. In terms of value to the public purse, proven cases of fraud regarding separation and dependant allowance tended to be low, and the audit procedures were proven to be efficient for their day. From the outset of the separation and dependant allowance scheme, other agencies were employed to externally audit claims made by wives and dependants. For example, Old Age Pension Assessors and local education authority school inspectors’ were employed to check the validity of claims made and the number of dependants entitled to separation and dependant allowances in households. The internal accounts at regimental pay offices and local Territorial Force Associations were monitored by the War Office Finance Branch through the Inspector of Regimental Pay Offices and by officials from the Exchequer and Audit Department. The History of Separation Allowance pointed out that: ’How great the element of fraud and exaggeration has been and its effect on the cost of the scheme cannot be determined, but it is to be hoped it has been less than it might be inferred from the veritable chorus of such statements as ‘The War Office is being robbed right and left’, ‘masses of misstatement,’ ‘tissues of falsehood’ which have appeared in letters and reports or the contention of a defending solicitor in the case of prosecution as early as 1915 that, it was unfair to single out some when it is notorious everyone is doing it.’ In the absence of exact evidence on the point, opinion necessarily rests on the degree and type of experience and in so large a field there is always the possibility that experience has been too limited for judgement of the whole, and the angle from which the matter is viewed too narrow.

The Griffiths Report highlights internal audits or ‘Pay Office checks’. For example at every regimental pay office ‘every item posted to a soldier’s account is checked by a “group checker”’. However, 15 per cent were checked by a supervising clerk and debits on a soldier’s account of 5 shillings and upwards, or postings having a continuous effect, i.e. changes in the rates of pay, were checked by the officer in charge of a section, either a lady superintendent, civilian acing paymaster, or assistant paymaster APD. Staff from the directing staff of the regimental paymaster checked, unannounced, a selection of the ledger sheets at frequent intervals.

Nevertheless, the Griffiths Report criticised the over-checking of audit by the regimental paymaster’s staff and considered the ‘expense was out of proportion to their effectiveness’, whereas the group check ‘seems to be carried out in a perfunctory manner, for … it overlooks as many errors as it detects’. Despite the complexities of a bureaucratic system that arose with the expansion in the breadth and scope of soldiers’ pay and dependant allowances during the Great War, the efficiency and stability of the pay and allowance system was perhaps due to the women who were employed in regimental pay offices and other APD establishments during the period 1914 to 1920. The bureaucratic system could have easily collapsed under the complexities of the structure and the frustrations due to the volume of enquiries and missing documents, together working in what was, in many cases, unsatisfactory accommodation.

The women employed within the regimental pay offices and other Army Pay Department establishments provided the stability within the labour force, both civilian and military. This included women clerks who were mainly employed on low-level mechanical clerical tasks that included the operation of the Slip System. Hinchliffe rarely mentioned women in his history of the Royal Army Pay Corps, and a more contemporary observer, ‘Behind the Scenes’, again, is not too complimentary about women who arrived at RPO Lichfield in 1915, when apparently a thousand of the Regimental Paymaster’s 1200 APC men were taken away from him and he had to scour the locality for women to take their places. ‘Behind the Scenes’ contends that he collected women of all sorts and sizes from Birmingham and neighbouring towns, who in most cases had no knowledge of clerical work and came from domestic services or were factory workers, Behind the Scenes complained that They took endless time to train. Some were so raw that pounds were placed in the shillings columns and vice versa, but there was no other material available, and he had to make the best of it … [However he happily concluded that] They, eventually turned out well, but their training was a slow and trying business.

These were probably the women who administered and managed the Slip System, which was perhaps the most innovative achieving of Army pay administration of its time. The deployment of ‘Heath Robinson’ technology similar to the Slip System of the army pay offices during the Great War was also used by the code breakers at Bletchley Park during the Second World War who used similar slips and kept them with their pencils and rulers in jam jars, and their files in shoe boxes.

Asquith was adamant that conscription should be delayed as long as possible. When it finally came in 1916, it caused the Liberal split. Nevertheless a mainly conscripted British Army from mid-1916 until the Armistice and beyond also remained loyal. Even those battalions of mainly conscripts who embarked on the British North Russian Expeditionary Force in 1919 remained loyal. This included the 17th (Service) Battalion, The King’s Liverpool Regiment whose ranks still included previous striking dock and transport workers from the pre-1914 ‘Great Unrest’ and volunteered as part of Kitchener’s Army. Pedersen is correct in her analysis that the temporary separation allowance system established during the First World War has gone almost unnoticed by historians. This includes the scale and scope of the reforms, which cost the taxpayer some half a billion pounds. Indeed Pedersen commented that

“

By the Armistice, allowances were absorbing some 120 million pounds per year, a figure roughly comparable to two-thirds of the total annual expenditure of central government in the pre-war years.”

However, Pedersen points out that the separation and family allowance system did not meet the needs of women dependants and remained the ownership of the soldier as part of his reward for serving his country. But this is exactly what kept the British soldier loyal; ownership was with the soldier and not the wife or other dependant. The concept of ownership is important when assessing the loyalty of the fighting soldier, and this was the philosophy behind the temporary cessation of ‘off the strength marriage’ and the equally temporary reform of the allowance system, rather than reflecting the real economic needs of the wife, official and unofficial, and other dependents.

The concession on the rates for 1914 and 1915 demonstrated the government’s acceptance of the contention, that, as one Liberal MP put it, there would be a more speedy and general rally to the Colours, if you relieve their minds of the men who, for many reasons, anxious to serve their country, have justly felt that their first duty was to their home, their wives and their children.

The system that developed from August 1914 was far more generous and liberal in nature than the previous demarcation of ‘off the strength marriage’. Waites suggested that the system of military separation and family allowances reduced the burden of hardship. so that “

By November 1914, the revival of men’s employment and the regular payment of servicemen’s separation allowances had greatly eased working class hardship.”

The final analysis to support the argument put forward in this article is that the system of an efficient pay and allowance system prevented any mass mutiny in the British Army in the field from 1914 to 1919. Although Pedersen pointed to long delays, particularly in Birmingham, which caused ‘far more distress than the disturbed state of trade’, she never mentions the mobile pay offices that were used to ease the congestion of separation claims.

Generally the role Army Pay Services during the Great War and their impact on contemporary domestic society is not a crowded area of academic or military search, having attracted little attention from historians generally. The strength of the two corps, the APD and APC that represented the Army Pay Services did not initially expand with the corresponding expansion of the British Army and remained at its peacetime strength until well into 1915.

Another example given within this area of argument is the destruction by fire of the Regimental Pay Office, (RPO), in Dublin, situated at Linen Hall Barracks, during the week of the Easter Rising in late April 1916. Within hours of its destruction, Army Pay Services staff were drafted from Britain for temporary duty in Dublin where, with the original staff of the Dublin pay office, and quickly restored a functioning pay office using temporary documentation and duplicate documentation held by Irish battalion orderly rooms, possibly causing some considerable inconvenience for those battalions on active service. All Irish regiments remained loyal throughout the Great War. The British press, reporting on the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Uprising, noted the loyalty of Irish regiments and Irishmen serving with the British Army.

To summarise it is necessary to reiterate Pedersen’s argument about separation allowances and the Great War where the British state made a decisive commitment to the articulation of this gendered system of welfare provision. It did so inadvertently through the extension and administration of universal, need-blind benefits –known as ‘separation allowances’- for the wives and children of soldiers and sailors. However the decision to introduce need-blind benefits of separation and family allowances (Pedersen did not mention the dependent allowances), made by Asquith supported by the Coalition government was to motivate loyalty in fighting soldiers on the front line and to maintain the social fabric and domestic loyalty on the home front. Despite the cost of the allowances scheme, the ultimate objective of having a generous, almost late 20

th century, welfare state system in place during the years of conflict from 1914 to 1920 was achieved. Both the British Army and British society remained loyal amid the horrors of a modern industrialised global war. The benefit of the unprecedented separation allowance system during the Great War resulted in the total loyalty of the fighting British Army. There was no mass mutiny in the ranks of the British Army or major civil unrest at home.

Conclusion

The argument that the system of separation and family allowance was the major reason why the British Army remained loyal during the First World War is a new direction in assessing whether this was the catalyst that kept the British Army loyal during the Great War. The conditions of the operational front were at the very least, deplorable, where casualty rates were astronomical. Despite this the British Army remained loyal apart from a small number of local disturbances.

It is interesting to note that the pay, separation and dependant system of the British Army, which temporarily evolved during the Great War, was unique. The Griffiths Report, in its penultimate assessment of Pay Office efficiency during the Great War, attempted comparisons with contemporary civil establishments without success as noted in the recommendations;

“

It may here be remarked that in order to compare the army system with that of a big civil organization with scattered personnel, the Committee has examined the methods adopted by the Great Railway Company for paying its employees and bringing the expenditure to account. It finds, however, that the company’s system would not meet the peculiar needs of

the army. The industrial world appears to officer no counterpart to the army as regards the conditions of service, and particularly the extent to which the employee’s domestic economy is controlled by his employers, and the Committee is agreed that no useful purposes would be served by extending its enquiries in this connection.”

The human machinery that made efficiency shine through an otherwise complex and what could have been an inefficient system, were the personnel of the Army Pay Services, both civilian and military.

In answering the original question posed by Professors Prost and Winter’s to why the British Army did not mass mutiny during the Great War, one needs to look further into the introduction and administration of the separation and dependent allowance system as well as the vehicle of its implementation is such an efficient manner.

Perhaps final comments from two officers’ pre-1914 Regular Army officers who served during the Great War further underpin the argument put forward in this article. The first was a junior gunner officer who served in operational theatres and later became a senior RAPC officer, Brigadier R. W. Hackett; the second, a senior regimental paymaster who served mainly in home stations during the Great War, Colonel R. Daubeny CBE. In a speech given in 1965, Hackett commented:

“

All that War the [Army Pay] Corps used pen and ink and I who was at the receiving end can say that they got us our cash wherever we were and an account of our men’s pay and handled an immense job exceedingly well.”

The final word is Daubeny’s who, in 1934, wrote in retirement that

“

When Germany cracked the crack began at the back of the house, not at the front. The first line British soldier knew that his home could be kept going – the German had no such knowledge or trust and his power of resistance and strength weakened. The Paymaster knew that the [British] soldier would receive his pay no matter where he might be serving, whether his account balanced or not. It was therefore sound policy to ensure the family allowances were issued promptly.”

Notes on contributor

John Black is an independent scholar who served in the British Regular Army (Royal Army Medical Corps) as a senior non-commissioned officer, seeing operational service in Sarawak during the Indonesian Confrontation and later in Norther Ireland. Following military service he became a secondary school teacher of business and history and later researcher at the University of the West of England Bristol. He holds a doctorate through the Open University.

[Top]