Pay Services during WW2

In 1920, both the Army Pay Department and the Army Pay Corps were granted the prefix of ‘Royal’ by the King in recognition of their services during the First World War. In that same year, the two separate organisations were merged into the Royal Army Pay Corps (R.A.P.C.).

All the officers of the R.A.P.C. qualified as paymasters. The head of the corps, who held the rank of Major General, was titled the ‘Chief Paymaster at the War Office and Inspector of Army Pay Offices’. Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, there were the following numbers of officers in the corps:

11 Chief Paymasters (in the rank of Colonel);

43 Staff Paymasters (Lieutenant Colonels (First Class) and Majors (Second Class);

86 Paymasters (Captains);

49 Assistant Paymasters (mainly Lieutenants).

There were a few other officers re-employed as paymasters and cashiers, making a total two-hundred and thirty-nine officers. In addition, there were one-thousand, one-hundred and forty-seven other ranks and five-hundred and eighty civilians.

Members of the R.A.P.C. were employed at formation level, for example, each division had one paymaster (usually in the rank of Captain) and one non-commissioned officer as cashier. These two personnel ran the Divisional Field Cash Office. Their function was to issue cash to Imprest Holders and authorised officers. In addition, they converted currency to that of the country in which the division was then serving. For example, when a division moved from France to Belgium in September 1944, all the French Francs held in the division had to be exchanged for Belgian Francs.

The 53 (Welsh) Infantry Division during the campaign in North West Europe had one-hundred and fifty imprest (account) holders, plus some eight-hundred officers who were entitled to be paid from the divisional cash offices. The soldiers were paid at Pay Parades held within their own units.

The Divisional Field Cash Office also receives cash from the Army Post Office, N.A.A.F.I., Y.M.C.A., canteens, officer’s shops and from individual units. As an example, the 53 (Welsh) Infantry Division in 1944 had one-hundred and fifty customers who paid in money to the cash office.

In an average month, the divisional cash office of the 53 Infantry Division received 2,522,360 Marks (£63,058 sterling equivalent) from one-hundred and fifty ‘customers’ and made payments of 8,547,800 Marks (£213,695 sterling equivalent) to two-thousand, two-hundred and twenty ‘customers’.

By the end of the Second World War, the R.A.P.C. had grown to over two-thousand officers, eighteen thousand other ranks, thirteen thousand members of the Auxiliary Territorial Force and six and half thousand civilians.

WW2 differed from WWI in that there were widely dispersed area of operations from the start. Paymasters and their staff accompanied the Field Army wherever it went. By far the biggest problem was the lack of suitable clerical labour and where to site the Pay Offices. Pay offices were established in France, and cashiers were located in the Western Desert, North Africa, India with Field Offices attached to the Formations.

At the outbreak of the 1939/45 war the modified London System was in use. In order to understand the problems which faced the Royal Army Pay Corps in the last war, it is necessary to paint the backcloth to the scene of the Army of the 1930s. Although without doubt the Munich crisis gave the country a severe jolt, it is not unkind to say that, despite conscription, the Army was reoccupied with the quiet regular rhythm of the trooping seasons and an existence and a training programme that were based on organisations and weapons that served well enough in previous wars.

This army was not to escape the repercussions of the social revolution which was to overtake Britain in the late 1940s. The strength of the Regular Army in 1939 was 175,000, the majority of which was stationed in the United Kingdom, Egypt and India. Garrisons of course existed in many other places but their sizes were relatively insignificant.

The magnitude of the Corps' task in the war will be realised when it is mentioned that the Army was to expand from its pre-war figure of 175,000 to one and a half million a year later and by the end of the war it was to rise to nearly three millions. In 1939, the total staff employed on Other Rank account maintenance was 1,200, this was to grow to 40,000 by 1915. What of the Pay System? A change had to be made from the modified London System to Loose Leaf Accounts. In fact, the Shrewsbury System, discarded in 1929 for reasons of staff economy, was reintroduced. To start with, it was only Units that were on active service who took into use AB64 Part Il and the Acquittance Roll; in 1940, however, when invasion of the country was threatened, the rest of the Army came on to the system.

Just the same problems that faced the Army Pay Department in 1914 faced the Royal Army Pay Corps in 1939 and 1940. Staff was pitifully inadequate and the 600 Supplementary Reservists, 318 Territorial Army, 165 Militia and our A.T.S. (T.A.) were naturally unable to cope with a rapid expansion of the Army. If it had not been for the respite granted by the "phoney" war of 1939 to the spring of 1940, the Corps would, without doubt, have been in serious difficulties. Ideally, Army Pay Offices need to be accommodated in peace-time in buildings that can be retained on mobilisation. In 1939/45 this ideal was not achieved and it seems that Commands were totally unaware of the effects of mobilisation and expansion of such Offices. Great difficulty was to be experienced in finding suitable accommodation where moves had to be made. Two large Offices were moved between September and December, 1939. On one of these moves a lorry carrying documents overturned and papers were scattered over a wide area, many being destroyed or lost, resulting in a large reconstruction of accounts having to be undertaken. It may interest readers of these articles to know that in August, 1940, Regimental Pay Offices in the United Kingdom were at Ashford, Bournemouth, Edinburgh, Exeter, Finsbury, Foots Cray, Brompton Road, Ilfracombe, Kidderminster, Leicester, London, Manchester, Nottingham, Perth, Preston, Radcliffe, Reading, Shrewsbury and York.

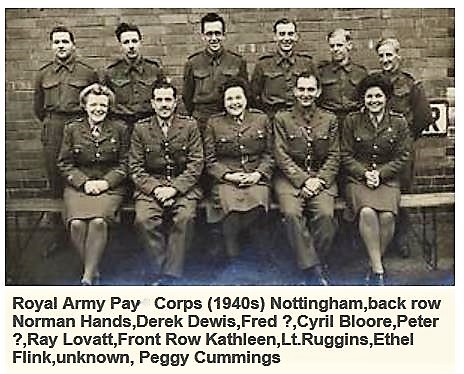

Photo: Ray Lovatt

Photo: Ray Lovatt

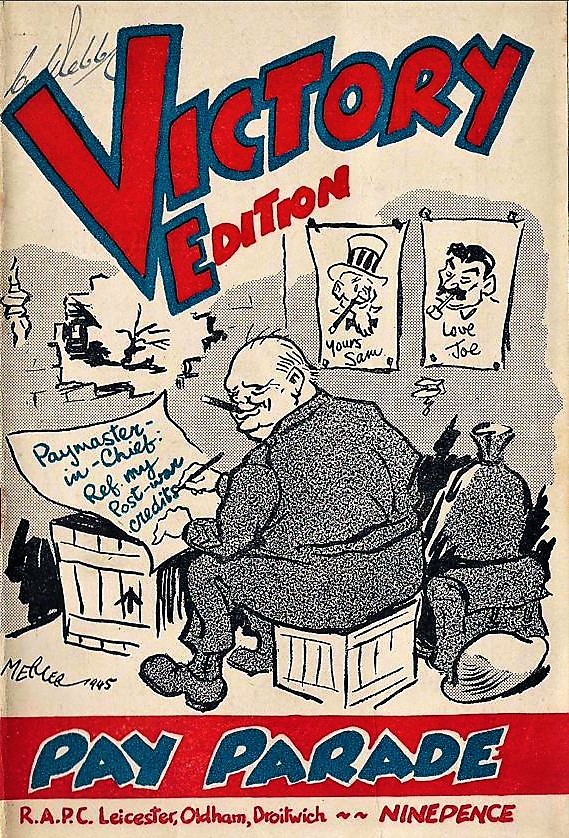

RAPC Leicester, Oldham & Droitwich "Pay Parade" Magazine 1945

This image appears on Dr Vincent Holyoak's website:

Leicester in WW2

Whilst on the subject of the Offices themselves, it is not inappropriate to mention the air raids. In October, 1940, the London Office received a direct hit which killed an A.T.S. and a RA.P.C. Sergeant and injured 150 other people. In November of the same year, 12 Other Ranks were killed in the Leicester office; three Officers were killed in the Officers' Accounts Office in Manchester, and in May, 1941, an Other Rank was killed in Belfast. This list is not exhaustive and only records a few of the incidents. One direct result of the danger from air raids was that Regimental Paymasters in the United Kingdom were instructed to prepare duplicate account cards against the event of the destruction of accounts. These cards were stored in bank vaults, strong-rooms and safe places other than in the buildings with the originals. This instruction was to remain in force until April, 1945.

(Ed:

Whilst we cannot substantiate the claim about the London or Belfast Office being directly hit in an air raid, the death of the 12 Other Ranks in Leicester and the three Officers in Manchester were definitely not as a result of air strikes on the Leicester and Manchester offices, but on the accommodation in which personnel were billeted see here: major incidents)

An extract from the Daily Herald of the 2nd October, 1940, proves the necessity to remember that members of the Corps are soldiers first and foremost. "In Central London yesterday, I found 40 or 50 soldiers helping in demolition work, but they were not Royal Engineers, they were men of the Royal Army Pay Corps. A police officer told me the soldiers had done more in an hour than he had seen some demolition squads perform in a whole day, and these are the so called soft-job boys of the Army, he added.". Finally, in discussing the Offices themselves, mention must be made that the then Colonel-in-Chief, Her Royal Highness Princess Arthur of Connaught, visited the Regimental Pay Offices, London, in 1943.

What about the technical difficulties with which the Corps was confronted ' The change-over in some Offices just before the war from punched card accounting meant that less trained staff were available. The staff in Offices which had always been on the manual system, had a thorough knowledge of Pay procedures and they were able to supervise hastily recruited junior staff. In 1940, the Paymaster-in-Chief was to make representations that R.A.P.C. intakes contained many men who had no Clerical experience and he quoted cases of milk-roundsmen, plasterers, hosiery knitters, barmen, antique dealer and a grave-digger! As a result of these representations the quality of the Corps intakes did improve.

Early in the war there was a great deal of correspondence from soldiers' wives and dependants about their allowances. The problem of sorting out these queries was aggravated by the fact that many of the relatives failed to quote the soldier's particulars. A congestion of work in Post Offices and the family evacuation scheme added to the problem. However, the Corps had one method of communication denied to their fathers in 1914-1918, that was the B.B.C. Recourse to this method of putting over information about allowances was resorted to on several occasions. The hasty expansion of the Territorial Army just before mobilisation was administratively chaotic. Many companies were without any Army forms or regulations and in some cases Regimental Paymasters were unaware of the existence of such Units. On mobilisation some Units did absolutely nothing about pay! Some did make an enquiry as to the procedure to be followed in the absence of forms. The delay in allotting Army numbers by the Officers in Charge of Records was another cause of delay. In some cases (although not in nearly as many instances as in World War I) men were overseas before being given a number.

Another interesting development during the war was the adoption, for some pay documentation, of the Microgram Service. This obviated, to some extent, the delays which were brought about by very long lines of communication. Mention must be made of the "Process" System, by which soldiers' accounts were maintained. In effect this system is one whereby complicated processes are broken down into a large number of elemental tasks, each of which can be learnt by a relatively unskilled clerk. One of these processes was to become mechanised in 1944. This was the posting of debits and credits to soldiers' accounts. This part of the Process System was to continue, more or less unchanged, until the recent introduction of A.D.P.

Finally, after the war the release of soldiers was to present urgent problems. Release and Aftermath Wings were set up to cope with the closing of accounts and to deal with the inquiries from discharged soldiers.

It can be seen that the same problems have presented themselves time and again. Where should the soldier's account be kept, at the Unit or centrally ' Should the peace-time system be that which is used during a war! How should the Royal Army Pay Corps ensure it has an adequate reservoir of trained personnel to draw on in the event of an emergency!

"The above article first appeared in the RAPC Corps Journal in 1963"