The last man to do National Service

Richard Vaughan (second row, second from right) during his National Service 1961

Prince Harry recently called for National Service to be reintroduced, but would that be a good idea? Chris Stokel-Walker meets the last man officially discharged from National Service, 52 years ago.

Richard Vaughan was a fresh-faced 22-year-old when he was posted to the Royal Army Pay Corps' barracks at Devizes in Wiltshire on 17 November 1960.

Vaughan had just completed his exams, and with 162 others made up No 277 National Service Intake, the last group compelled to undergo National Service with the RAPC.

At 22, Vaughan was four years older than some of the other men he lined up with at Devizes. Like many in his unit, he had been granted a deferment to pass his exams to become a chartered accountant. Now 77, and running his own accounting firm in Bromley, Vaughan often looks back at the effect National Service had on him.

Richard Vaughan in military uniform

Richard Vaughan in military uniform

"Without experiencing what life would be like without going into the services, I can't say whether it changed me," he admits. "But it certainly opened your eyes to a completely different existence to working nine-to-five in an office. I would've got a nice job in commerce or industry. I was qualified. That was the biggest blow - I wasn't able to cash in on my qualification."

Richard Vaughan today

Most men, Vaughan included, took the posting in their stride. "I didn't come across many people who said: 'If I wasn't in here I could be this, that or the other'," he admits. "That didn't come into it. Most of our guys said, 'Well we're lumbered, we've got to make the best of it; let's enjoy it as best as we can.'"

Some soldiers-to-be were less happy - particularly those who were newly married, taken away from their wives for two years. "We bowled in wondering what was going on," Vaughan says. "It was a bit of an adventure."

1961: Passing out parade for 18 Platoon RAPC/TC (Vaughan front row, 2nd left)

National Service was introduced in 1939, as Britain entered World War Two, to redress a shortage of soldiers. Single men aged between 20 and 22 were called up to service, though the age range was extended to all men aged between 18 and 41 within a few months. In 1942, women between 20 and 30 were added to the list of those who could be conscripted, and the upper age range for men was extended to 51, all in the cause of fighting the world war.

Once the war was over, National Service remained. Men between 17 and 21 had to spend a year and a half in the armed forces to undergo training, and could be called up to war if needed for four subsequent years. By the 1950s, National Service took men into training for two full years. Nearly two million went through it.

"It served different purposes at different times," explains Richard Vinen, a historian at Kings College London, and author of a book on National Service in the post-war years. "Initially it was to train soldiers as a reserve force, and then it was to have them ready for immediate deployment, and then it was for colonial warfare."

By 1957, the process was winding down gradually. According to records collated by the Imperial War Museum, Richard Vaughan, by May 1963 a lieutenant with the Royal Army Pay Corps, was the last National Serviceman officially discharged from duty. (Vaughan is wary of saying that he is anything other than "the official last demobbed person" - he believes that other servicemen being treated in hospital, for example, could have been demobilised after he was.).

National Service was no longer needed. Birth rates had increased, but more than that war was changing - becoming increasingly technological. The forces needed professional soldiers with advanced skills - not conscripts who were often counting down the days until they went home.

"They didn't bring us in because the Cold War was still going on," explains Vaughan, "they brought us in because the law said to bring us in. When the Cold War was still roaring away, they stopped it. If conscription was still needed, why did they stop it?"

"It was also very unpopular," says Vaughan. Banishing conscription was one reason of many that Harold MacMillan's Conservative party won the 1959 election in such big numbers.

National Service has been well represented in popular culture. In the 1990 film The Krays, Reggie Kray, played by Martin Kemp, tells his commanding officer that "you've got nothing to say and you're saying it too loudly", before deserting. The real Krays were indeed called up in 1952, five years before conscription started to be wound down.

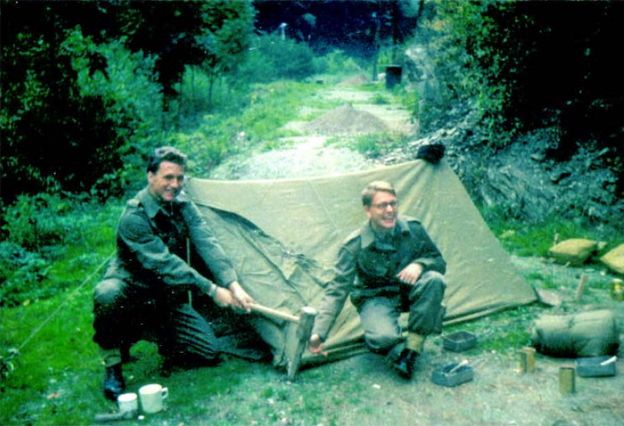

Vaughan (left) and friend assembling a tent

A less violent and more comic portrayal of conscription was the inept buffoonery of the servicemen in Carry on Sergeant, a 1959 film that lampooned National Service.

But the very words continue to have political resonance. The idea of bringing back some form of National Service has been floated as a response to wayward youth on many occasions.

While the case for a form of military conscription seems far-fetched in an era when the professional armed forces are being cut, schemes for mandatory community work have been suggested. Former home secretary David Blunkett advocated a national volunteer service in response to the 2011 riots, suggesting: "It should become an integral part of growing up in Britain, a rite of passage into adulthood, just as National Service used to be for the 1950s generation."